使用衍射深度神经网络的全光机器学习.pdf

免费下载

OPTICAL COMPUTING

All-optical machine learning using

diffractive deep neural networks

Xing Lin

1,2,3

*, Yair Rivenson

1,2,3

*, Nezih T. Yardimci

1,3

, Muhammed Veli

1,2,3

,

Yi Luo

1,2,3

, Mona Jarrahi

1,3

, Aydogan Ozcan

1,2,3,4

†

Deep learning has been transforming our ability to execute advanced inference tasks using

computers. Here we introduce a physical mechanism to perform machine learning by

demonstrating an all-optical diffractive deep neural network (D

2

NN) architecture that can

implement various functions following the deep learning–based design of passive

diffractive layers that work collectively. We created 3D-printed D

2

NNs that implement

classification of images of handwritten digits and fashion products, as well as the function

of an imaging lens at a terahertz spectrum. Our all-optical deep learning framework can

perform, at the speed of light, various complex functions that computer-based neural

networks can execute; will find applications in all-optical image analysis, feature detection,

and object classification; and will also enable new camera designs and optical components

that perform distinctive tasks using D

2

NNs.

D

eep learning is one of the fastest-growing

machine learning methods (1). This ap-

proach uses multilayered artificial neural

networks implemented in a computer to

digitally learn data representation and ab-

straction and to perform advanced tasks in a

manner comparable or even superior to the per-

formance of human experts. Recent examples in

which deep learning has made major advances in

machine learning include medical image analysis

(2), speech recognition (3), language transla-

tion (4), and image classification (5), among others

(1, 6). Beyond some of these mainstream appli-

cations, deep learning methods are also being

used to solve inverse imaging problem s (7–13).

Here we introduce an all-optical deep learning

framework in which the neural network is phys-

ically formed by multiple layers of diffractive

surfaces that work in collaboration to optically

perform an arbitrary function that the network

can statistically learn. Whereas the inference and

prediction mechanism of the physical network

is all optical, the learning part that leads to its

design is done through a computer. We term this

framework a diffractive deep neural network

(D

2

NN) and demonstrate its inference capabil-

ities through both simulations and experiments.

Our D

2

NN can be physically created by using

several transmissive and/or reflective layers (14),

where each point on a given layer either trans-

mits or reflects the incoming wave, representing

an artificial neuron that is connected to other

neurons of the following layers through optical

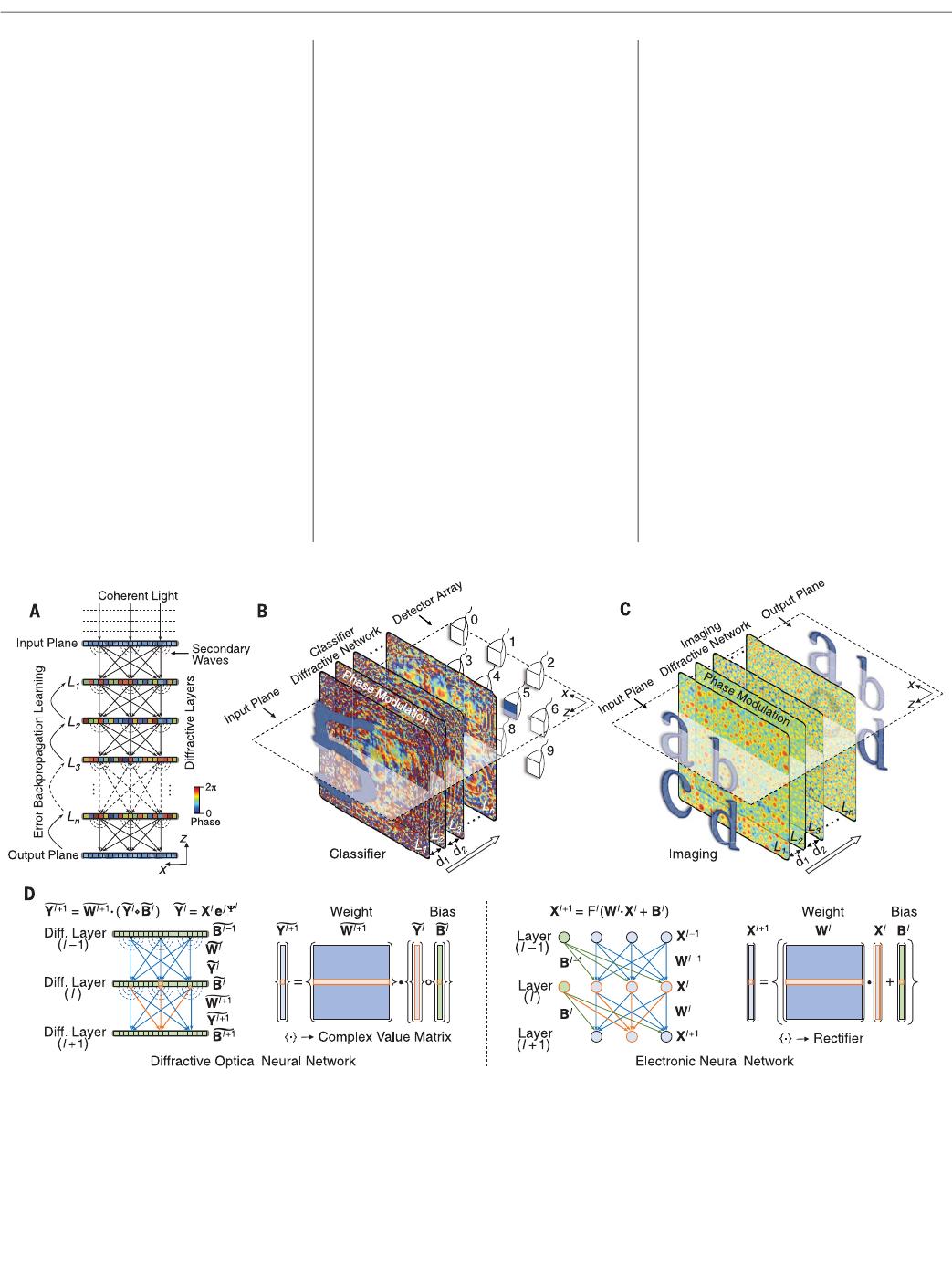

diffraction(Fig.1A).Inaccordancewiththe

Huygens-Fresnel principle, our terminolog y is

based on each point on a given layer acting as a

secondary source of a wave, the amplitude and

phase of which are determined by the product

of the input wave and the complex-valued trans-

mission or reflection coefficient at that point [see

(14) for an analysis of the waves within a D

2

NN].

Therefore, an artificial neuron in a D

2

NN is con-

nected to other neurons of the following layer

through a secondary wave modulated in ampli-

tude and phase by both the input interference

pattern created by the earlier layers and the local

transmission or reflection coefficient at that point.

As an analogy to standard deep neural networks

(Fig. 1D), one can consider the transmission or

reflection coefficient of each point or neuron as

amultiplicative“bias” term, which is a learnable

network parameter that is iteratively adjusted

during the training process of the diffractive net-

work, using an error back-propagation method.

After this num erical training phase, th e D

2

NN

design is fixed and the transmission or reflec-

tion coefficients of the neurons of all layers are

determined. This D

2

NN design—once physically

fabricated using techniques such as 3D-printing

or lithography—can then perform, at the speed

of light, the specific task for which it is trained,

using only optical diffraction and passive optical

components or layers that do not need po wer,

thereby creating an efficient and fast way of

implementing machine learning tasks.

In general, the ph ase and amplitude of ea ch

neuron can be learnable parameters, providing

a complex-valued modulation at each layer,

which improves the inference performance of

the diffractive network (fig. S1) (14). For coher-

ent transmissive networks with phase-only mod-

ulation, each layer can be approximated as a thin

optical element (Fig. 1). Through deep learning,

the phase values of the neurons of each layer of

the diffractive network are iteratively adjusted

(trained) to perform a specific function by feed-

ing training data at t he input layer and then

computing the network’s output through optical

diffraction. On the basis of the calculated error

with respect to the target output, determined by

the desired function, the network structure and

its neuron phase values are optimized via an error

back-propagation algorithm, which is based on

the stochastic gradient descent approach used

in conventional deep learning (14 ).

To demonstrate the performance of the D

2

NN

framework, we first trained it as a digit classifier

to perform automated classification of hand-

written digits, from 0 to 9 (Figs. 1B and 2A). For

this task, phase-only transmission masks were

designed by training a five-layer D

2

NN with

55,000 images (5000 validation images) from the

MNIST (Modified National Institute of Stan-

dards and Technology) handwritten digit data-

base (15). Input digits were encoded into the

amplitude of the i nput field to the D

2

NN, and

the diffractive network was trained to map input

digits into 10 detector regions, one for each digit.

The classification criterion was to find the de-

tector with the maximum optical signal, and this

was also used as a loss function during the net-

work training (14).

After training, the design of the D

2

NN digit

classifier was numer ically tested using 10,000

images from the MNIST test dataset (which were

not used as part of the training or validation

image sets) and achieved a classification accu-

racy of 91.75% (Fig. 3C and fig. S1). In addition to

the classification performance of the diffractive

network, we also analyzed the energy distribu-

tion observed at the network output plane for the

same 10,000 test digits (Fig. 3C), the results of

which clearly demonstrate that the diffractive

network learned to focus the input energy of

each handwritten digit into the correct (i.e., the

target) detector region, in accord with its train-

ing. With the use of complex-valued modulation

and increasing numbers of layers, neurons, and

connections in the diffractive network, our classi-

fication accuracy can be further improved (figs.

S1 and S2). For example, fig. S2 demonstrates a

Lego-like physical transfer learning behavior for

D

2

NN framework, where the inference perform-

ance of an already existing D

2

NN can be further

improved by adding new diffractive layers—or, in

some cases, by peeling off (i.e., discarding) some

of the existing layers—where the new layers to

be added are trained for improved inference

(coming from the entire diffractive network: old

and new layers). By using a patch of two layers

added to an existing and fixed D

2

NN design (N =

5 layers), we improved our MNIST classification

accuracy to 93.39% (fig. S2) (14); the state-of-the-

art convolutional neural network performance

has been reported as 99.60 to 99.77% (16–18).

More discussion on reconfiguring D

2

NN designs

is provided in the supplementary materials (14).

Following these numerical results, we 3D-

printed our five- layer D

2

NN design (Fig. 2A),

with each layer having an area of 8 cm by 8 cm,

followed by 10 detector regions defined at the

output plane of the diffractive network (Figs. 1B

and 3A). We then used continuous-wave illumi-

nation at 0.4 THz to test the network’sinference

performance (Figs. 2, C and D). Phase values of

RESEARCH

Lin et al., Science 361, 1004–1008 (2018) 7 September 2018 1of5

1

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University

of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA.

2

Department

of Bioengineering, University of California, Los Angeles, CA

90095, USA.

3

California NanoSystems Institute (CNSI),

University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA.

4

Department of Surg ery, David Geffen School of

Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA.

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

†Corresponding author. Email: ozcan@ucla.edu

Downloaded from https://www.science.org on August 29, 2024

each layer’s neurons were physically encoded

using the relative thickness of each 3D-printed

neuron. Numerical testing of this five-layer D

2

NN

design achieved a classification accuracy of 91.75%

over ~10,000 test images (Fig. 3C). To quantify the

match between these numerical testing results

and our experiments, we 3D-printed 50 hand-

written digits (five different inputs per digit),

selected among the same 91.75% of the test images

for which numerical testing was successful. For

each input object that is uniformly illuminated

with the terahertz source, we imaged the output

plane of the D

2

NN to map the intensity distri-

bution for each detector region that is assigned

to a digit. The results (Fig. 3B) demonstrate the

success of the 3D-printed diffractive neural net-

work and its inference capability: The average

intensity distribution at the output plane of the

network for each input digit clearly reveals that

the 3D-printed D

2

NN was able to focus the input

energy of the beam and achieve a maximum sig-

nal at the corresponding detector region assigned

for that digit. Despite 3D-printing errors, possible

alignment issues, and other experimental error

sources in our setup (14), the match between the

experimental and numerical testing of our five-

layer D

2

NN design was found to be 88% (Fig. 3B).

This relatively small reduction in the perform-

ance of the experimental network compared to

our numerical testing is especially pronounced

for the digit 0 because it is challenging to 3D-

print the large void region at t he center of the

digit. Similar printing challenges were also ob-

served for other digits that have void regions;

e.g.,6,8,and9(Fig.3B).

Next, we tested the classification performance

of D

2

NN framework with a more complicated

image dataset—i.e., the Fashion-MNIST dataset

(19), which includes 10 classes, each representing

a fashion product (t-shirts, trousers, pullovers,

dresses, coats, sandals, shirts, sneakers, bags, and

ankle boots; see fig. S3 for sample images). In gen-

eral, for a coherently illuminated D

2

NN, we can use

the amplitude and/or phase channels of the input

plane to represent data to be classified or processed.

In our digit classification results reported earlier,

input objects were encoded by using the ampli-

tude channel, and to demonstrate the utility of

the phase channel of the network input, we en-

coded each input image corresponding to a fash-

ion product as a phase-only object modulation

(14). Our D

2

NN inference results (as a function of

the number of layers, neurons, and connections)

for classification of fashion products are sum-

marizedinfigs.S4andS5.Toprovideanexample

of our performance, a phase-only and a complex-

valued modulation D

2

NN with N = 5 diffractive

layers (sharing the same physical network dimen-

sions as the digit classification D

2

NN shown

in Fig. 2A) reached an accuracy of 81.13 and

86.33%, respectively (fig. S4). By increasing the

number of diffractive lay ers to N = 1 0 and the

total number of neurons to 0.4 million, our

classification accuracy increased to 86.60% (fig.

S5). For convolutional neural net–based standard

deep learning, the state-of-the-art performance

for Fashion-MNIST classification accuracy has

been reported as 96.7%, using ~8.9 million learn-

able parameters and ~2.5 million neurons (20).

To experimentally demonstrate the perform-

ance of fashion product classification using a

physical D

2

NN, we 3D-printed our phase-only

five-layer design and 50 fashion products used

as test objects (five per class) on the basis of the

same procedures employed for the digit classi-

fication dif fractive network (Fig s. 2A and 3),

except that each input object information was

encoded in the phase channel. Our results are

summarized in Fig . 4, revealing a 90% match

between the experimental and numerical testing

of our five-layer D

2

NN design, with five errors

out of 50 fashion products. Compared with digit

classification (six errors out of 50 digits; Fig. 3),

this experiment yielded a slightly better match

Lin et al., Science 361, 1004–1008 (2018) 7 September 2018 2of5

Fig. 1. Diffractive deep neural networks (D

2

NNs). (A)AD

2

NN comprises

multiple transmissiv e (or reflectiv e) layer s, where each point on a given layer acts

as a neuron, with a complex -valu ed transmission (or reflection) coefficient. The

transmis sion or reflection coefficients of each layer can be traine d by using deep

learning to perform a function between the input and output planes of the

network. After this learning phase, the D

2

NN design is fixed; once fabricated or

3D-printed, it performs the learned function at the speed of light. L, layer. (B and

C) We trained and experimen tally implemented different types of D

2

NNs:

(B) classifier (for handwritten digits and fashion pro ducts) and (C) imager .

d,distance.(D) Comparison between a D

2

NN and a convention al neural network

(14). Based on coherent waves, the D

2

NN operates on complex -valued inputs,

with multiplicative bias terms. Wei ghts in a D

2

NN are based on free-space

diffraction and determine the interference of the secondary waves that ar e phase-

and/or amplitude-modulated by the previous layers. “o” denotes a Hadamard

product operation. “Ele ctroni c neural network” ref ers to the convention al neural

netwo rk virtually implemented in a computer. Y, optical field at a given layer;

Y, phase of the optical field; X, amplitude of the optical field; F, nonlinear rectifier

function [see (14) for a discussion of optical nonlinearit y in D

2

NN].

RESEARCH | REPORT

Downloaded from https://www.science.org on August 29, 2024

of 5

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

文档被以下合辑收录

评论