VLDB2024_《The Art of Latency Hiding in Modern Database Engines》_腾讯云.pdf

免费下载

The Art of Latency Hiding in Modern Database Engines

Kaisong Huang

Simon Fraser University

kha85@sfu.ca

Tianzheng Wang

Simon Fraser University

tzwang@sfu.ca

Qingqing Zhou

DB365000

sendtoqq@gmail.com

Qingzhong Meng

Tencent Inc.

freemeng@tencent.com

ABSTRACT

Modern database engines must well use multicore CPUs, large main

memory and fast storage devices to achieve high performance. A

common theme is hiding latencies such that more CPU cycles can

be dedicated to “real” work, improving overall throughput. Yet

existing systems are only able to mitigate the impact of individual

latencies, e.g., by interleaving memory accesses with computation

to hide CPU cache misses. They still lack the joint optimization of

hiding the impact of multiple latency sources.

This paper presents MosaicDB, a set of latency-hiding tech-

niques to solve this problem. With stackless coroutines and carefully

crafted scheduling policies, we explore how I/O and synchroniza-

tion latencies can be hidden in a well-crafted OLTP engine that

already hides memory access latency, without hurting the per-

formance of memory-resident workloads. MosaicDB also avoids

oversubscription and reduces contention using the coroutine-to-

transaction paradigm. Our evaluation shows MosaicDB can achieve

these goals and up to 33× speedup over prior state-of-the-art.

PVLDB Reference Format:

Kaisong Huang, Tianzheng Wang, Qingqing Zhou, and Qingzhong Meng.

The Art of Latency Hiding in Modern Database Engines. PVLDB, 17(3):

577-590, 2023.

doi:10.14778/3632093.3632117

PVLDB Artifact Availability:

The source code, data, and/or other artifacts have been made available at

hps://github.com/sfu-dis/mosaicdb.

1 INTRODUCTION

Various kinds of latency exist in modern database engines [

13

,

30

,

41

,

46

,

55

,

57

] that target machines with large main memory, fast SSDs

and multicore CPUs. When the working set ts in memory, memory

is the primary home of data and various important data structures

(e.g., indexes and version chains [

62

]) where memory blocks at

random locations are chained using pointers. As a result, data stalls

caused by pointer chasing in turn become a major bottleneck [

27

].

Since hardware prefetchers are ineective for pointer chasing [

5

,

32

,

54

], modern CPUs oer prefetching instructions [

24

] that allow

software to proactively move data from memory to CPU caches in

advance. Importantly, such instructions are asynchronous, allowing

software prefetching approaches to overlap computation and data

fetching [

5

,

27

,

32

,

48

]. Coupled with lightweight coroutines [

25

],

latency-optimized OLTP engines [

21

] use software prefetching to

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International

License. Visit hps://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ to view a copy of

this license. For any use beyond those covered by this license, obtain permission by

emailing info@vldb.org. Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). Publication rights

licensed to the VLDB Endowment.

Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, Vol. 17, No. 3 ISSN 2150-8097.

doi:10.14778/3632093.3632117

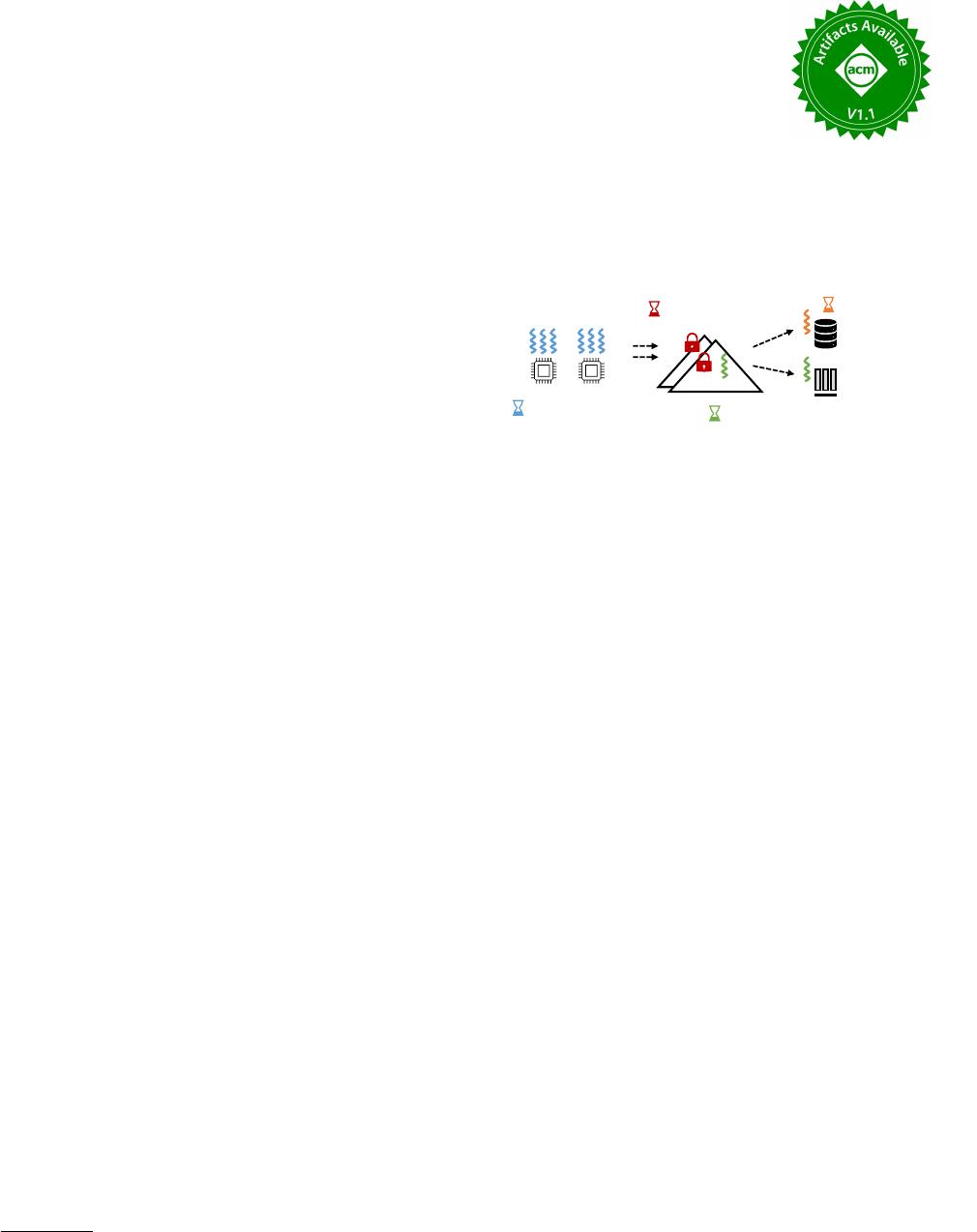

Indexes

(a) Oversubscription

and OS scheduling

Storage-resident data

Memory-resident data

(b) Synchronization

Transaction

threads:

(c) CPU cache misses (data stalls)

(d) Storage I/O

Figure 1: Main sources of latency in memory-optimized OLTP

engines. Software prefetching can eectively hide data stalls

(c). MosaicDB further mitigates the impact of other latencies

(a, b, d) while preserving the benets of software prefetching.

hide data stalls with the coroutine-to-transaction execution model

in an end-to-end manner. In these systems, transactions are mod-

eled as coroutines that are suspendable and resumable at various

code locations. Each worker thread runs a scheduler that switches

between coroutines (transactions) upon potential last-level cache

misses, improving overall throughput by overlapping data fetching

of one transaction with another’s on-CPU computation. Notably,

the cost of suspending and switching between stackless coroutines

is very low (similar to calling a function), allowing the engine to

gain net performance increase, sometimes by up to 2× [21].

1.1

Just Hiding Memor y Latency Is Not Enough

Despite the signicant performance improvement observed by end-

to-end latency-optimized engines [

21

], these systems are still inad-

equate and leave many unexplored opportunities in further hiding

more types of latency, as shown in Figure 1.

First, as data size grows, it becomes necessary to support larger-

than-memory databases. As a result, in Figure 1(c–d) a transaction

may access both memory- and storage-resident data. Yet existing

latency-optimized OLTP engines based on software-prefetching

are mostly designed to hide data stalls caused by memory accesses

(0.1

𝜇

s level) shown in Figure 1(c), without considering dierent

levels of data movement latency, especially storage accesses at the

10

𝜇

s to ms level. As we elaborate later, a direct addition of storage

accesses to an end-to-end OLTP engine optimized for hiding mem-

ory latency would cancel out the benet of software prefetching or

even yield worse throughput than without using prefetching at all.

Second, in addition to the complexity caused by a mix of dierent

data access latencies, the software architecture of a database engine

can also induce latency during forward processing. As shown in Fig-

ure 1(a), CPU cores may be oversubscribed to run more threads than

the degree of hardware multiprogramming, causing OS scheduling

activities. The use of synchronization primitives can also lead to

additional delays. For example, in Figure 1(b) the number of (re)tries

(consequently, latency) to acquire a contended spinlock [

53

] could

be arbitrarily long depending on the workload, making system

behavior highly unpredictable.

577

These issues limit the applicability of latency-optimized database

engines. Future engines should further address other sources of

latency, and more importantly, do so while preserving the benets

of existing latency-hiding techniques, such as software prefetching.

1.2

MosaicDB: Latency Hiding at the Next Level

This paper presents MosaicDB, a multi-versioned, latency-optimized

OLTP engine that hides latency from multiple sources, including

memory, I/O, synchronization and scheduling as identied earlier.

To reach this goal, MosaicDB consists of a set of techniques that

could also be applied separately in existing systems.

MosaicDB bases on the coroutine-to-transaction paradigm [

21

]

to hide memory access latency. On top of that, we observe that

the key to eciently hiding I/O latency without hurting the per-

formance of memory-resident transactions is carefully scheduling

transactions such that the CPU can be kept busy while I/O is in

progress. To this end, MosaicDB proposes a pipelined scheduling

policy for coroutine-oriented database engines. The basic ideas are

(1) keeping admitting new requests in a pipelined fashion such that

each worker thread always works with a full batch of requests, and

(2) admitting more I/O operations to the system only when there

is enough I/O capacity (measured by bandwidth consumption or

IOPS). This way, once the storage devices are saturated, MosaicDB

only accepts memory-resident requests, which can benet from

software prefetching. By carefully examining alternatives in later

sections, we show how these seemingly simple ideas turned out to

be eective and became our eventual design decision.

To avoid latency caused by synchronization primitives and OS

scheduling, MosaicDB leverages the coroutine-to-transaction para-

digm to regulate contention and eliminate the need for background

threads. Specically, each worker thread can work on multiple

transactions concurrently, but only one transaction per thread will

be active at any given time. This avoids oversubscribing the system

by limiting the degree of multiprogramming to the amount of hard-

ware parallelism (e.g., number of hardware threads). Consequently,

the OS scheduler will largely be kept out of the critical path of the

OLTP engine because context switching only happens in the user

space as transactions are suspended and resumed by the worker

threads. Using this architecture, MosaicDB also further removes

the need for dedicated background threads (e.g., log ushers) which

were required by pipelined commit [

26

] that is necessary to achieve

high transaction throughput without sacricing durability: cleanup

work such as log ushes can be done using asynchronous I/O upon

transaction commit, which will then suspend and be resumed and

fully committed only when the I/O request is nished.

We implemented MosaicDB on top of CoroBase [

21

], a latency-

optimized OLTP engine that hides memory latency using software

prefetching. Compared to baselines, on a 48-core server, MosaicDB

maintains high throughput for memory-resident transactions, while

allowing additional storage-resident transactions to fully lever-

age the storage device. Overall, MosaicDB achieves up to 33

×

higher throughput for larger-than-memory workloads; with given

CPU cores, MosaicDB is free of oversubscription and outperforms

CoroBase by 1.7

×

under TPC-C; MosaicDB has better scalability

under high contention workloads, with up to 18% less contention

and 2.38× throughput compared to state-of-the-art.

Although MosaicDB is implemented and evaluated on top of

CoroBase, the techniques can be separately applied in other systems.

For example, contention regulation can be adopted by systems that

use event-driven connection handling where the total number of

worker threads will never exceed the number of hardware threads.

We leave it as future work to explore how MosaicDB techniques

can be applied in other systems.

1.3 Contributions

This paper makes four contributions.

1

We quantify the impact of

various sources of latency identied in memory-optimized OLTP

engines, beyond memory access latency which received most atten-

tion in the past.

2

We propose design principles that preserve the

benets of software prefetching to hide memory latency and hide

storage access latency at the same time.

3

In addition to memory

and storage I/O, we show how software database engine architec-

ture could be modied to avoid the latency impact of synchroniza-

tion and OS scheduling.

4

We build and evaluate MosaicDB on

top of an existing latency-optimized OLTP engine to showcase

the eectiveness of MosaicDB techniques in practice. MosaicDB is

open-source at hps://github.com/sfu-dis/mosaicdb.

2 BACKGROUND

We begin by clarifying the type of systems that our work is based

upon and assumptions. We then elaborate the main sources of

latencies that MosaicDB attempts to hide, followed by existing

latency-optimized designs that motivated our work.

2.1 System Architectures and Assumptions

We target memory-optimized OLTP engines that both (1) leverage

large DRAM when data ts in memory and (2) support larger-than-

memory databases when the working set goes beyond memory.

Larger-Than-Memory Database Engines. There are mainly

two approaches to realizing this. One is to craft better buer pool

designs [

37

,

46

] which use techniques like pointer swizzling [

18

,

28

]

and low-overhead page eviction algorithms [

37

,

58

] to approach in-

memory performance when data ts in DRAM, while otherwise pro-

viding graceful degradation and fully utilizing storage bandwidth.

The other approach employs a “hot-cold” architecture [

14

,

31

] that

does not use a buer pool, and separates hot and cold data whose

primary homes are respectively main memory and secondary stor-

age (e.g., SSDs). In essence, a hot-cold database engine consists

of a “hot store” that is memory-resident (although persistence is

still guaranteed) and an add-on “cold store” in storage. A transac-

tion then could access data from both stores. However, note that

both “stores” use the same mechanisms for such functionality as

concurrency control, indexing and checkpointing, inside a single

database engine without requiring cross-engine capabilities [

64

].

In this paper, we focus on the hot-cold architecture and leave it as

future work to explore the buer pool based approach.

Hot-Cold Storage Engines. Figure 2 shows the design of ER-

MIA [

30

], a typical hot-cold system that employs multi-versioned

concurrency, in-memory indexing and indirection arrays [

50

] to

support in-memory data (hot store) and storage-resident data (cold

store). Many other systems [

13

,

14

,

39

,

40

] follow similar designs.

An update to the database will append a new in-memory record

578

of 14

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

文档被以下合辑收录

评论