03. Convolutional Neural Networks at Constrained Time Cost.pdf

40墨值下载

Convolutional Neural Networks at Constrained Time Cost

Kaiming He, Jian Sun

Microsoft Research

In industrial and commercial scenarios, engineers and developers are

often faced with the requirement of constrained time budget. This paper

investigates the accuracy of CNN architectures at constrained time cost dur-

ing both training and testing stages. Our investigations involve the depth,

width, filter sizes, and strides of the architectures. Because the time cost

is constrained, the differences among the architectures must be exhibited

as trade-offs between those factors. For example, if the depth is increased,

the width and/or filter sizes need to be properly reduced. In the core of our

designs is “layer replacement” - a few layers are replaced with some oth-

er layers that preserve time cost. Based on this strategy, we progressively

modify a model and investigate the accuracy through a series of controlled

experiments. This not only results in a more accurate model with the same

time cost as a baseline model, but also facilitates the understandings of the

impacts of different factors to the accuracy.

From the controlled experiments, we draw the following empirical ob-

servations about the depth. (1) The network depth is clearly of high priority

for improving accuracy, even if the width and/or filter sizes are reduced to

compensate the time cost. This is not a straightforward observation even

though the benefits of depth have been recently demonstrated, because in

previous comparisons the extra layers are added without trading off other

factors, and thus increase the complexity. (2) While the depth is important,

the accuracy gets stagnant or even degraded if the depth is overly increased.

This is observed even if width and/filter sizes are not traded off (so the time

cost increases with depth).

We obtain a model that achieves 11.8% top-5 error (10-view test) on

ImageNet and only takes 3 to 4 days training on a single GPU. Our model

is more accurate and also faster than several competitive models in recent

papers. Our model has 40% less complexity than “AlexNet” and has 4.2%

lower top-5 error.

Trade-offs between Depth and Filter Sizes

We first investigate the trade-offs between depth d and filter sizes s. We

replace a larger filter with a cascade of smaller filters. We denote a layer

configuration as: n

l−1

· s

2

l

· n

l

, which is also its theoretical complexity with

n denoting the filter number and s denoting the filter size.

An example replacement can be written as the complexity involved:

256 · 3

2

· 256 (1)

⇒ 256 · 2

2

· 256 + 256 · 2

2

· 256.

This replacement means that a 3×3 layer with 256 input/output channels is

replaced by two 2×2 layers with 256 input/output channels.

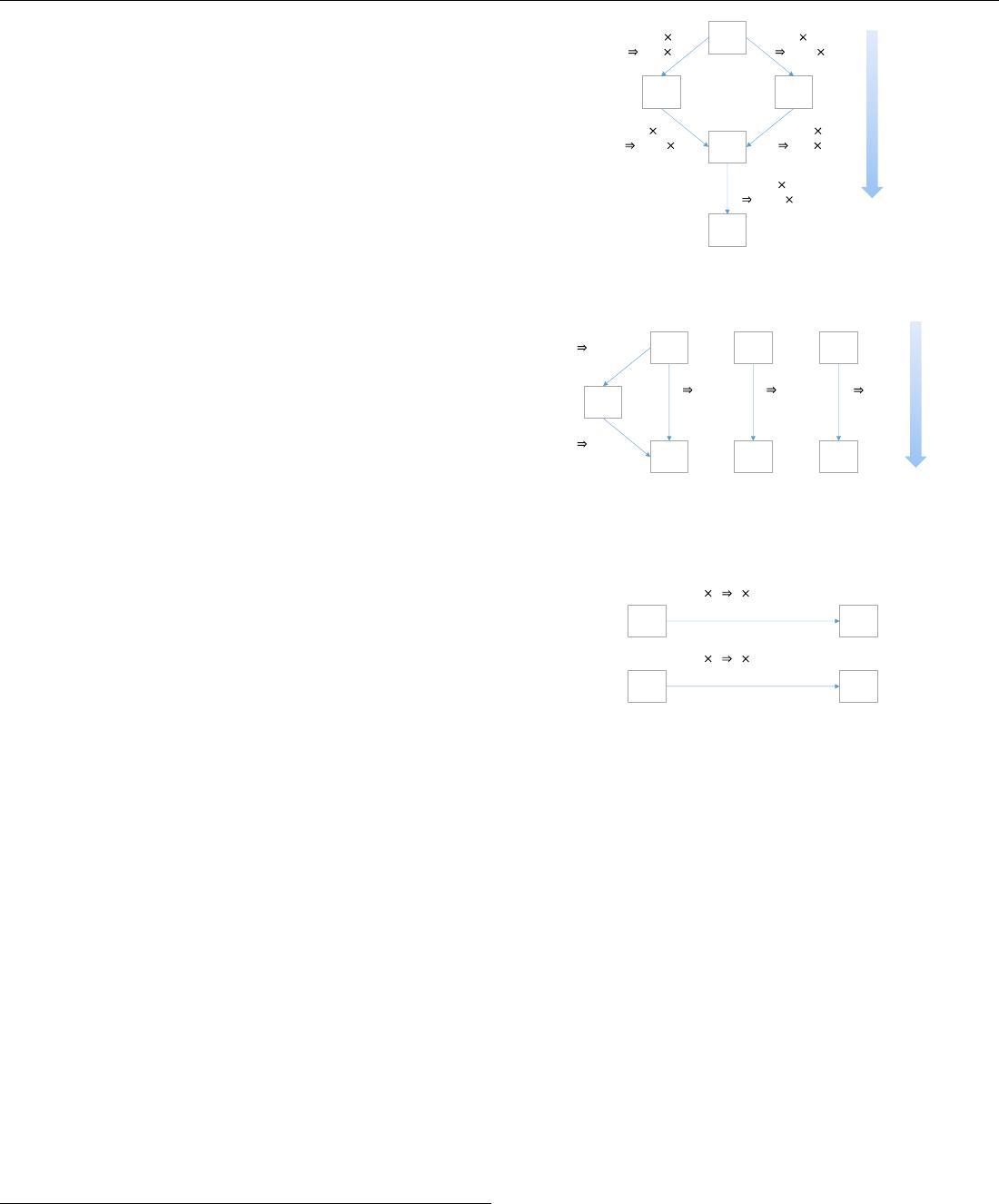

Fig. 1 summarizes the relations among the models A, B, C, D, and E.

Here deep models have smaller filter sizes. When the time complexity is

roughly the same, the deeper networks with smaller filters show better re-

sults than the shallower networks with larger filters.

Trade-offs between Depth and Width

Next we investigate the trade-offs between depth d and width n. We increase

depth while properly reducing the number of filters per layer, without chang-

ing the filter sizes. We replace the three 3×3 layers with six 3×3 layers. The

complexity involved is:

128 · 3

2

· 256 + (256 · 3

2

· 256) × 2 (2)

= 128 · 3

2

· 160 + (160 · 3

2

· 160) × 4 + 160 · 3

2

· 256.

Here we fix the number of the input channels (128) of the first layer, and

the number of output filters (256) of the last layer, so avoid impacting the

This is an extended abstract. The full paper is available at the Computer Vision Foundation

webpage

.

ƚŚƌĞĞϯ ϯ

Ɛŝdž Ϯ Ϯ

ϱ

ϱ

ƚǁŽϯ ϯ

ϱ

ϱ

ƚǁŽϯ ϯ

ƚŚƌĞĞϯ

ϯ

ƐŝdžϮ Ϯ

ƚǁŽϯ

ϯ

ĨŽƵƌϮ Ϯ

ϭϱ͘ϵ

ϭϰ͘ϯ

ϭϰ͘ϵ

ϭϯ͘ϵ

ϭϯ͘ϯ

ĚĞĞƉĞƌΘ

ƐŵĂůůĞƌĨŝůƚĞƌƐ

Figure 1: The relations of the models about depth and filter sizes.

ĚĞĞƉĞƌΘ

ŶĂƌƌŽǁĞƌ

&

ϭϰ͘ϴ

ϭϱ͘ϵ

'

ϭϰ͘ϳ

ϭϰ͘ϯ

,

ϭϰ͘Ϭ

ϭϯ͘ϵ

/

ϭϯ͘ϱ

ϯ ϲůĂLJĞƌƐ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϯͿ

ϲ

ϴ ůĂLJĞƌƐ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϯͿ

ϯ

ϴ ůĂLJĞƌƐ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϯͿ

Ϯ ϰůĂLJĞƌƐ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϮͿ

Ϯ

ϰůĂLJĞƌƐ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϮͿ

Figure 2: The relations of the models about depth and width.

Ϯ Ϯ ϯ ϯ͕ŶĂƌƌŽǁĞƌ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϯͿ

Ϯ Ϯ ϯ ϯ͕ŶĂƌƌŽǁĞƌ

;ŽŶƐƚĂŐĞϮͿ

ϭϰ͘ϵ

&

ϭϰ͘ϴ

ϭϯ͘ϯ

/

ϭϯ͘ϱ

Figure 3: The relations of the models about width and filter sizes.

previous/next stages. With this replacement, the width reduces from 256 to

160 (except the last layer).

Fig. 2 summarizes the relations among the models of A, F, G, H, and

I. Here the deeper models are narrower. We find that increasing the depth

leads to considerable gains, even the width needs to be properly reduced.

Trade-offs between Width and Filter Sizes

We can also fix the depth and investigate the trade-offs between width and

filter sizes. The models B and F exhibit this trade-off on the last six convo-

lutional layers:

128 · 2

2

· 256 + (256 · 2

2

· 256) × 5 (3)

⇒ 128 · 3

2

· 160 + (160 · 3

2

· 160) × 4 + 160 · 3

2

· 256.

This means that the first five 2×2 layers with 256 filters are replaced with

five 3×3 layers with 160 filters.

Fig.

3 shows the relations of these models. Unlike the depth that has a

high priority, the width and filter sizes (3×3 or 2×2) do not show apparent

priorities to each other.

More trade-offs involving depth, width, filter sizes, strides, and pooling are

investigated in the main paper.

of 1

40墨值下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论