VLDB2024_SALI: A scalable adaptive learned index framework based on probability models_腾讯云.pdf

免费下载

SALI: A Scalable Adaptive Learned Index Framework based on

Probability Models

Jiake Ge

♠♥

, Huanchen Zhang

♦§

, Boyu Shi

♣♥

, Yuanhui Luo

♠♥

, Yunda Guo

♠♥

, Yunpeng Chai

♣♥∗

,

Yuxing Chen

+

, Anqun Pan

+

♠

Key Laboratory of Data Engineering and Knowledge Engineering, MOE, China

♣

Engineering Research Center of Database and Business Intelligence, MOE, China

♥

School of Information, Renmin University of China

§

China and Shanghai Qi Zhi Institute

♦

Tsinghua University

+

Tencent Inc.

gejiake@ruc.edu.cn, huanchen@tsinghua.edu.cn, shiboyu5687@ruc.edu.cn, losk@ruc.edu.cn,

guoyunda@ruc.edu.cn, ypchai@ruc.edu.cn, axingguchen@tencent.com, aaronpan@tencent.com

ABSTRACT

The growth in data storage capacity and the increasing demands for

high performance have created several challenges for concurrent

indexing structures. One promising solution is learned indexes,

which use a learning-based approach to t the distribution of stored

data and predictively locate target keys, signicantly improving

lookup performance. Despite their advantages, prevailing learned

indexes exhibit constraints and encounter issues of scalability on

multi-core data storage.

This paper introduces SALI, the Scalable Adaptive Learned Index

framework, which incorporates two strategies aimed at achieving

high scalability, improving eciency, and enhancing the robust-

ness of the learned index. Firstly, a set of node-evolving strategies

is dened to enable the learned index to adapt to various work-

load skews and enhance its concurrency performance in such sce-

narios. Secondly, a lightweight strategy is proposed to maintain

statistical information within the learned index, with the goal of

further improving the scalability of the index. Furthermore, to vali-

date their eectiveness, SALI applied the two strategies mentioned

above to the learned index structure that utilizes ne-grained write

locks, known as LIPP. The experimental results have demonstrated

that SALI signicantly enhances the insertion throughput with 64

threads by an average of 2

.

04

×

compared to the second-best learned

index. Furthermore, SALI accomplishes a lookup throughput similar

to that of LIPP+.

CCS CONCEPTS

• Information systems → Data access methods.

∗

Yunpeng Chai is the corresponding author.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for prot or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the rst page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM

must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish,

to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specic permission and/or a

fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

Conference SIGMOD ’24, June 09–15, 2024, Santiago, Chile

© 2024 Association for Computing Machinery.

ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-XXXX-X/18/06. .. $15.00

https://doi.org/XXXXXXX.XXXXXXX

KEYWORDS

Learned Index; Probability Models; Adaptive Index

ACM Reference Format:

Jiake Ge

♠♥

, Huanchen Zhang

♦§

, Boyu Shi

♣♥

, Yuanhui Luo

♠♥

, Yunda Guo

♠♥

,

Yunpeng Chai

♣♥∗

, Yuxing Chen

+

, Anqun Pan

+

. 2024. SALI: A Scalable Adap-

tive Learned Index Framework based on Probability Models. In Proceedings

of In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Management of Data

(Conference SIGMOD ’24). ACM, Santiago, Chile, 17 pages.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the exponential growth of the data volume today, ecient

indexing data structures are crucial for a big data system to sup-

port timely information retrieval. To improve the performance and

memory eciency of traditional tree-based indexes, Kraska et al.

introduced a learned index, called the Recursive Model Indexes

(RMI) that uses machine learning models to replace the internal

nodes of a B+tree [

15

,

20

]. An outstanding problem of the original

RMI is that it is static: inserting or updating a key in the index

requires a signicant portion of the data structure to rebuild, thus

limiting the use cases of the learned index.

Previous work has proposed two strategies to address the up-

datability issue of learned indexes. The rst (i.e., the buer-based

strategy) is to accommodate new entries in separate insert buers

rst to amortize the index reconstruction cost. XIndex [

36

] and

FINEdex [

21

] fall into this category. The other strategy (i.e., the

model-based strategy) adopted by ALEX [

3

] and LIPP [

39

] is to re-

serve slot gaps within nodes to handle new entries with an in-place

insertion. Upon an insert collision (i.e., the mapped slot is already

occupied), ALEX reorganizes the node by shifting the existing en-

tries, while LIPP utilizes a chaining scheme, creating a new node for

the corresponding slot to transform the last-mile search problem

into a sub-tree traversal problem.

We found, however, that none of the above index designs scale at

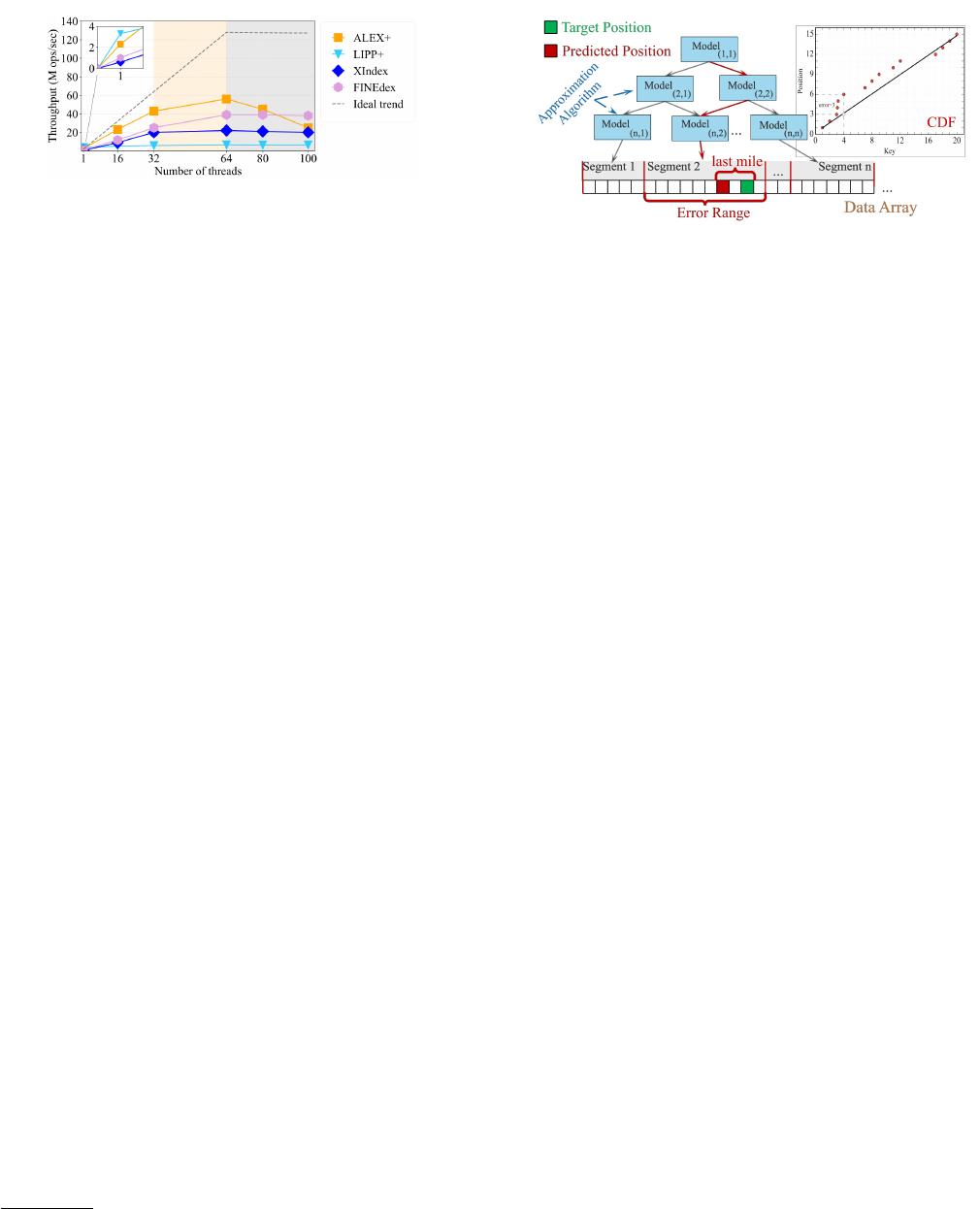

a high concurrency. We performed an experiment where we insert

200 million random integer keys into a learned index, with a varying

number of threads each time. Figure 1 shows the results. Note that

the number of threads in the grey area of the gure is larger than

the number of hardware threads of the machine. This is common

in practice as a database/key-value server typically handles a large

number of user connections simultaneously.

1

arXiv:2308.15012v2 [cs.DB] 5 Sep 2023

Conference SIGMOD ’24, June 09–15, 2024, Santiago, Chile Jiake Ge and Huanchen Zhang, et al.

Figure 1: Write-only performance of state-of-the-art learned

indexes on the FACE dataset [

11

]. The evaluation is con-

ducted on a two-socket machine with two 16-core CPUs.

As shown in Figure 1, indexes with a buer-based strategy (i.e.,

XIndex and FINEdex) exhibit inferior base performance and worse

scalability compared to those with a model-based strategy (i.e.,

ALEX+ and LIPP+

1

). This shows that a larger margin of predic-

tion errors prevents scaling because the concurrent “last mile”

searches saturate the memory bandwidth quickly which becomes

the system’s bottleneck [38].

The problem is solved in LIPP+ where each position prediction

is accurate (i.e., no “last mile” search). However, LIPP+ requires

maintaining statistics, such as access counts and collision counts,

in each node to trigger node retraining to prevent performance

degradation. These per-node counters create high contention

among threads and cause severe cacheline ping-pong [

38

]. The

model-based strategy in ALEX+ requires shifting existing entries

upon an insert collision. Therefore, ALEX+ must acquire coarse-

grained write locks for this operation. As the number of threads

increases, more and more threads are blocked, waiting for those

exclusive locks.

In this paper, we propose SALI, the Scalable Adaptive Learned

Index framework based on probability models to solve the scalabil-

ity issues in existing solutions. To solve the scalability bottleneck

of maintaining per-node statistics, we developed lightweight prob-

ability models that can trigger node retraining and other structural

evolving operations in SALI with accurate timing (as if the timing

were determined by accurate statistics). In addition, we developed

a set of node-evolving strategies, including expanding an insert-

heavy node to contain more gaps, attening the tree structure

for frequently-accessed nodes, and compacting the rarely-touched

nodes to save memory. SALI applies these node-evolving strate-

gies adaptively according to the probability models so that it can

self-adjust to changing workloads while maintaining excellent scal-

ability. Finally, SALI adopts the learned index structure that utilizes

ne-grained write locks, i.e., LIPP+, to validate the eectiveness of

the aforementioned two strategies. Note that the lightweight proba-

bility models and node-evolving strategies are highly versatile and

can be applied to various index scenarios, as detailed in Section 5.

Our microbenchmark with real-world data sets shows that SALI

improves the insertion throughput with 64 threads by 2

.

04

×

on

average compared to the second-best learned index, i.e., ALEX+,

while achieving a lookup throughput comparable to LIPP+.

We make three primary contributions in this paper. Firstly, we

proposed SALI, a high-concurrency learned index framework de-

signed to improve the scalability of learned indexes. Secondly, we

1

ALEX+ and LIPP+ are concurrent implementations of ALEX and LIPP, respec-

tively [38].

Figure 2: The scheme of the learned index.

dened a set of node-evolving strategies in addition to model re-

training to allow the learned index to self-adapt to dierent work-

load skews. Thirdly, we replaced the per-node statistics in existing

learned indexes with lightweight probability models to remove the

scalability bottleneck of statistics maintenance while keeping the

timing accuracy of node retraining/evolving. Finally, we proved

the eectiveness of the proposed approaches by showing that SALI

outperforms the SOTA learned indexes under high concurrency.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 sum-

marizes the basics of learned indexes and further motivates the

scalability problem. Section 3 introduces the structure of SALI with

an emphasis on the node-evolving strategies and the probability

models. Section 4 presents our experimental results. Section 5 dis-

cusses the generalizability of the node-evolving strategies and the

probability models, as well as the limitations of SALI, followed

by a related work discussion in Section 6 Section 7 concludes the

paper. The source code of this paper has been made available at

https://github.com/YunWorkshop/SALI.

2 BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION

2.1 The principle of learned indexes

The core concept of the learned index is to employ a set of learning

models to estimate the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of

the stored data [

29

], allowing for the prediction of the data’s storage

location, as depicted in the CDF diagram on Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows the scheme for the learned index structure. Each

node, or only the lowest leaf nodes, stores the slope and intercept

of the linear function [

3

,

5

,

8

,

15

,

21

,

36

,

39

]. Each segment corre-

sponds to a linear model, which is responsible for the approximate

position of the target key. The index segments correspond to linear

models that estimate the target key’s position, eliminating the need

for multiple indirect search operations in traditional tree-based in-

dexes. This approach has the potential to improve indexed lookup

performance signicantly.

2.2 Scalable Evaluation of Learned Index

Structures

Currently, learned indexes demonstrate good performance in

single-threaded environments. However, their scalability remains

limited [

38

]. In this part, our objective is to conduct a thorough

investigation into the factors that contribute to the concurrent

performance bottlenecks in existing learned indexes. To achieve

this, we begin by introducing the insertion strategies employed in

learned indexes, along with their corresponding index structures,

as these design choices signicantly inuence the concurrent per-

formance of the indexes. Additionally, we conduct a comprehensive

2

of 17

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论