A刊TKDE 2025-Distributed_Semantic_Trajectory_Similarity_Search.pdf

免费下载

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE AND DATA ENGINEERING, VOL. XX, NO. XX, XXX XXXX 1

Distributed Semantic Trajectory Similarity Search

Shenghao Gong, Ziquan Fang, Liu Liu, Yaofeng Tu, Yunjun Gao, Senior Member, IEEE

Abstract—The proliferation of location-based services has

facilitated the generation of extensive semantic trajectories for

moving objects. In this paper, we investigate the problem of

semantic trajectory similarity search, a fundamental task of

trajectory analysis. The objective is to identify “similar” trajecto-

ries to a query trajectory by considering both spatial proximity

and semantic similarity. Existing studies predominantly utilize

keywords-based discrete semantic modeling, which fails to cap-

ture broader semantics, such as text descriptions. Moreover, these

studies typically develop search algorithms on a single machine,

resulting in limited processing capability.

To this end, we propose an effective framework to perform

distributed semantic trajectory similarity searches. We introduce

a novel method for representing semantic trajectories by em-

ploying both geographical sequences and semantic sequences.

This approach enhances spatial-semantic awareness in trajectory

modeling. Next, we implement the query framework in Spark

and propose a carefully designed two-phase, computation-aware

partitioning architecture. This is the first architecture to consider

both semantic and spatial aspects of trajectories, as well as

inter-trajectory distances, to guide the partitioning process. It

enables efficient pruning of most partitions in the cluster when

processing queries. Within each local partition, we construct an

ST-HNSW index to further accelerate queries. Our framework

supports three widely used trajectory distance measures: DTW,

LCSS, and EDR. Extensive experiments on two real and one

synthetic datasets demonstrate the significant advantages of our

design, achieving efficiency improvements of up to 1 to 3 orders

of magnitude over baseline and alternative approaches.

Index Terms—Trajectory Similarity Search, Distributed Com-

putation, Query Optimization

I. INTRODUCTION

W

ITH the proliferation of GPS devices, a large num-

ber of trajectories of vehicles and individuals have

been generated. Trajectory similarity search is a fundamental

functionality in trajectory databases [1]–[3], and is useful in

transportation and security fields, e.g., finding vehicles that

share similar routes to the query abnormal driving vehicle;

finding close contacts to the patient’s trajectory. Besides,

it is a fundamental operator for many downstream analy-

ses including clustering [4], pattern mining [5], and route

planning [6]. Overall, the community has devoted efforts

into spatial-aware trajectory similarity search [3], [7]–[12],

concentrating on searching for similar trajectories considering

spatial perspective.

Recently, the explosion of social networks and online maps

has augmented trajectories with semantic data [13], [14]. A

S. Gong and Z. Fang are with the School of Software Technology,

Zhejiang University, Ningbo 315048, China, E-mail: {gongshenghao, zq-

fang}@zju.edu.cn.

L. Liu and Y. Gao (Corresponding Author) are with the College of

Computer Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China, E-mail:

{liu2, gaoyj}@zju.edu.cn.

Yaofeng Tu is with the ZTE Corporation, Nanjing 210012, China, E-mail:

tu.yaofeng@zte.com.cn.

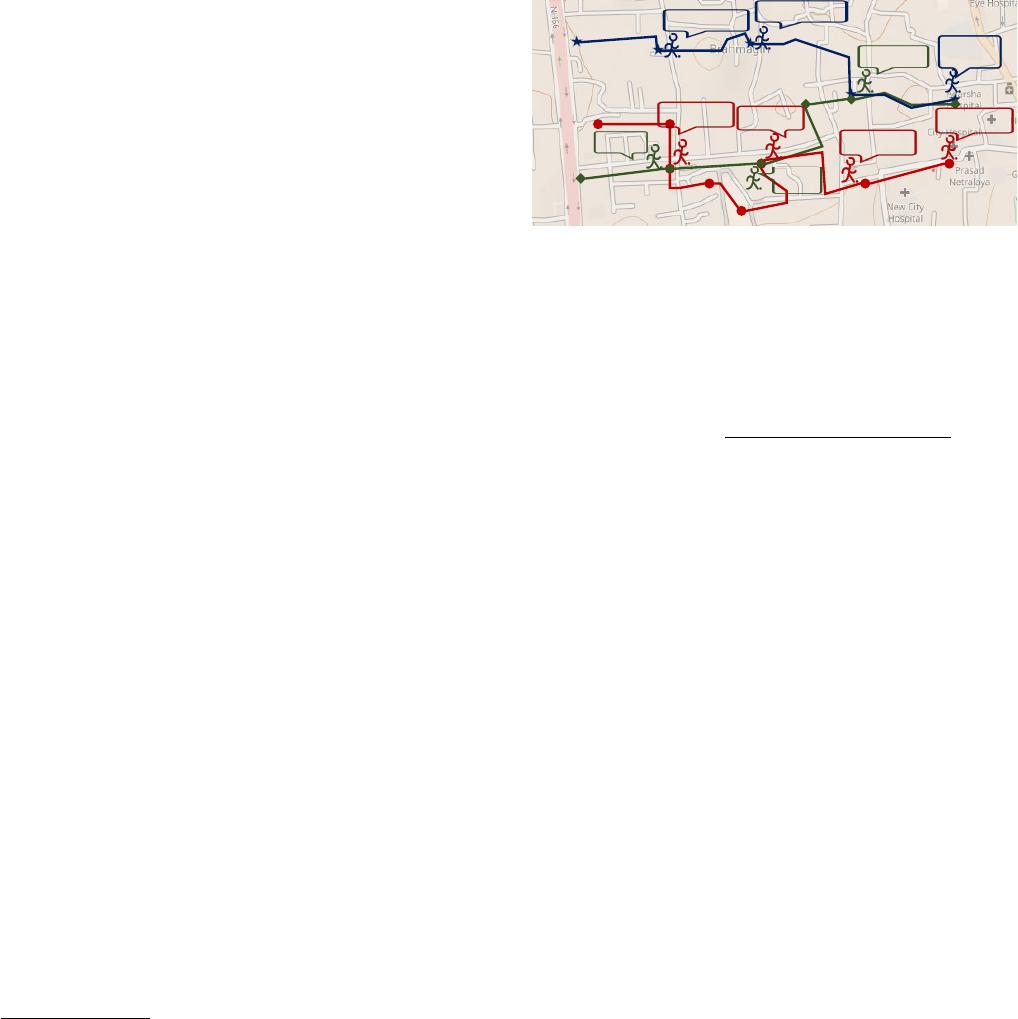

Coffee

Shop

Shopping

Mall

Government

College

Western

Restaurant

Sanskirt

College

Italian

Restaurant

Grocery

College

Market

𝜏

1

𝜏

𝜏

3

Chat with friends.

Try on a dress.

Listen to a lecture.

Delicious dinner.

Buy a coffee.

Drive in a

traffic jam.

Unload the sports

equipment.

Bump into a friend.

Clothing procurement.

Cooked to

perfection.

Fig. 1. A Toy Example of Three Semantic Trajectories

semantic trajectory is denoted by a sequence of locations

where each location is associated with semantic label(s) like

keywords and text descriptions. With semantic trajectories,

we can know not only where a user has been, but also

what he/she has done. In this paper, we investigate semantic

trajectory similarity search, which aims to find “similar”

trajectories considering spatial-semantic perspective. Overall,

semantic trajectory similarity search is extensively used in

online maps and social platforms like Google Maps [15] and

Foursquare [16]. There are also a multitude of semantic-based

travel planning apps, e.g., Wanderlog [17], Rome2Rio [18],

etc. Their behind idea is shown in Fig. 1, where three

trajectories exist, i.e., τ

1

–τ

3

. Although τ

1

and τ

2

are spatially

close, they express distant semantics and are thus preferred by

different groups. In contrast, τ

1

and τ

3

are semantically close

and may be recommended to the same group, like city tourists.

Consequently, it is important to consider spatial proximity and

semantic similarity when determining whether two trajectories

are similar to each other. However, when revisiting semantic

trajectory analyses [13], [14], [19]–[21], we identify three

unsolved challenges in terms of diverse semantic modeling,

scalable data processing, and query efficiency, as below.

Challenge I: How to model diverse semantic meanings?

As shown in Fig. 1, semantic trajectories exhibit diverse

meanings. For example, τ

1

records someone who chronically

“Chat with friends” at the Coffee Shop, “Try on a dress” at the

Shopping Mall, “Listen to a lecture” at the Sanskrit College,

and had dinner at the Italian Restaurant while commenting

“Delicious dinner”. As observed, two types of semantics exist,

i.e., keywords and text descriptions, where the former records

users’ locations and the latter records users’ activities. Note

that, even if τ

1

and τ

2

go through the same location, it is

possible to express different user activities. For example, τ

1

records someone who “Chat with friends” at the Coffee Shop

while τ

2

“Buy a coffee” without meeting anyone. Besides,

with the development of 5G technologies and location based

services (LBS), semantic information has become increasingly

diverse. However, existing studies [13], [19], [22] mostly

focus on keyword-based semantic modeling and cannot effec-

tively model text descriptions. In the above example, existing

This article has been accepted for publication in IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. This is the author's version which has not been fully edited and

content may change prior to final publication. Citation information: DOI 10.1109/TKDE.2025.3623108

© 2025 IEEE. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial intelligence and similar technologies. Personal use is permitted,

but republication/redistribution requires IEEE permission. See https://www.ieee.org/publications/rights/index.html for more information.

Authorized licensed use limited to: ZTE Corporation (One Dept). Downloaded on October 28,2025 at 06:50:47 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE AND DATA ENGINEERING, VOL. XX, NO. XX, XXX XXXX 2

methods directly model the activity “Chat with friends” with

discrete keywords including “Chat”, “with”, and “friends”.

Leaving aside the disruption of the semantic coherence of

sentences, we cannot enumerate all keywords. To address this

challenge, we propose a new method to model a semantic

trajectory into a geospatial sequence and a semantic sequence,

respectively. In a semantic sequence, we embed semantic texts

into vectors, capturing the rich and deep semantics. Then,

we combine the spatial and semantic similarity into a spatial-

semantic similarity metric, while supporting popular measures

including DTW [23], LCSS [24], and EDR [25].

Challenge II: How to design a scalable distributed se-

mantic trajectory similarity search framework? Compared

to raw trajectories that consist of locations, semantic trajec-

tories introduce semantic events, leading to a great increase

in data sizes. Taking the widely used trajectory datasets T-

drive [26] and GeoLife [27] as examples, enriching them with

semantics according to online map APIs [15], [28] leads to

10 × storage increase. Even worse, owing to the intricacy

involved in semantic distance computation, the calculation of

similarity between semantic trajectories entails higher com-

plexity. According to our experimental study, after incorpo-

rating semantic information into T-drive, the processing time

required for a random single query on a single machine

exceeds 2,000 seconds. As a result, semantic trajectories

may easily exceed the storage capacity and computational

capability of a single machine, necessitating a distributed

and scalable framework. However, most existing distributed

trajectory query processing approaches only support spatial-

aware distributed computation. They partition trajectory data

using methods such as IDs [29], round-robin [3], or techniques

based on separated trajectory points and Minimum Bounding

Rectangles (MBRs) [30], [31]. However, these methods are

unable to partition data based on the semantic information

of trajectories. As a result, most trajectories within the same

partition are semantically non-similar, leading to significant

redundant computation. On the other hand, existing semantic

trajectory query methods do not support large-scale distributed

processing and do not have pruning ability (i.e., partition

skipping) during partitioning. To address this challenge, we

propose a two-phase and computation-aware partitioning ar-

chitecture over Spark [32]. In contrast to existing trajec-

tory partitioning methods that typically use IDs [29], round-

robin [3], or methods based on separated trajectory points

and Minimum Bounding Rectangles (MBRs) [30], [33] to

perform direct trajectory partitioning, we leverage both the

fine-grained semantic and spatial features of trajectories, as

well as the inter-trajectory distances to enable two-phase and

computation-aware distributed partitioning.

Challenge III: How to accelerate the query process? With

the above computation-aware distributed data partitioning, the

input trajectory dataset is assigned to different partitions.

Given a query trajectory, it will be broadcast into relevant

partitions for parallel searching. This brings the idea of de-

signing an effective index in each partition for local pruning.

Existing studies typically build inverted indexes over keywords

and manage trajectories with multiple inverted files. In each

file, they build traditional trajectory indexes, including tree

indexes [34], [35] and grid indexes [36], [37]. However,

the traditional indexes cannot reduce the time complexity of

scanning a partition, but only reduce the number of evaluated

trajectories. To address this challenge, we extend the HNSW

index [38], which was proposed for vector retrieval, for

semantic trajectory similarity search. Specifically, in each data

partition, we organize trajectories into a nearest neighbor graph

by connecting trajectories that are close in spatial-semantic

distance with edges. Based on that, we build a semantic

trajectory oriented HNSW index, called ST-HNSW, where the

query starts at a node in the graph and iteratively traverses

its neighboring nodes. Besides, we also develop a series of

optimization techniques on ST-HNSW for further acceleration.

Overall, we revisit semantic trajectory similarity search

from semantic modeling, distributed partitioning, and opti-

mized query. And we make the following contributions.

• We propose an expressive semantic trajectory modeling

method. Then, we adopt a linear combination way to

calculate the spatial-semantic inter-trajectory similarities,

while supporting three trajectory distance measures.

• We build a distributed framework for semantic trajec-

tory similarity search, incorporating a novel two-phase,

computation-aware partitioning strategy, which enables

efficient query processing by allowing the pruning of

most irrelevant partitions when a query is executed.

• We develop the ST-HNSW index in each data partition for

local query acceleration. Besides, a series of optimization

techniques is designed to further speed up local queries.

• Extensive experiments on three large-scale datasets

demonstrate the effectiveness, efficiency, and scalability

of the proposed framework over competitors.

II. PRELIMINARIES

A. Problem Statement

When reviewing existing semantic trajectory representation

methods, there are individual-based forms [13], [14], [19],

[22], [39] and global-based forms [40], [41]. The definitions

of the two forms of semantic trajectory are as follows.

Definition 1. (Individual-based Semantic Trajectory) An

individual-based semantic trajectory is an ordered sequence

of points, i.e., τ = ⟨p

1

, p

2

, ..., p

n

⟩, where each point p

i

(1 ≤ i ≤ n) contains a location l

i

and an optional keyword

set K

i

. Here K

i

= {key

1

, key

2

, ...} is used to describe the

attributes of the corresponding location p

i

.

Definition 2. (Global-based Semantic Trajectory) A global-

based semantic trajectory is an ordered point sequence

associated with a description keyword set, i.e., τ =

{⟨p

1

, p

2

, ..., p

n

⟩, K

i

}, where K = {key

1

, key

2

, ...} is used to

describe the attributes of the whole trajectory.

Under the definition of semantic trajectories mentioned

above, STSS aims to find other similar trajectories in a

semantic trajectory dataset for a given query trajectory. The

definition is as follows.

Definition 3. (Semantic Trajectory Similarity Search,

STSS) Given a set of individual-based or global-based se-

mantic trajectories T , a query trajectory τ

q

, a positive integer

This article has been accepted for publication in IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. This is the author's version which has not been fully edited and

content may change prior to final publication. Citation information: DOI 10.1109/TKDE.2025.3623108

© 2025 IEEE. All rights reserved, including rights for text and data mining and training of artificial intelligence and similar technologies. Personal use is permitted,

but republication/redistribution requires IEEE permission. See https://www.ieee.org/publications/rights/index.html for more information.

Authorized licensed use limited to: ZTE Corporation (One Dept). Downloaded on October 28,2025 at 06:50:47 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

of 14

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论