01.Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition.pdf

50墨值下载

Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition

Kaiming He Xiangyu Zhang Shaoqing Ren Jian Sun

Microsoft Research

{kahe, v-xiangz, v-shren, jiansun}@microsoft.com

Abstract

Deeper neural networks are more difficult to train. We

present a residual learning framework to ease the training

of networks that are substantially deeper than those used

previously. We explicitly reformulate the layers as learn-

ing residual functions with reference to the layer inputs, in-

stead of learning unreferenced functions. We provide com-

prehensive empirical evidence showing that these residual

networks are easier to optimize, and can gain accuracy from

considerably increased depth. On the ImageNet dataset we

evaluate residual nets with a depth of up to 152 layers—8×

deeper than VGG nets [41] but still having lower complex-

ity. An ensemble of these residual nets achieves 3.57% error

on the ImageNet test set. This result won the 1st place on the

ILSVRC 2015 classification task. We also present analysis

on CIFAR-10 with 100 and 1000 layers.

The depth of representations is of central importance

for many visual recognition tasks. Solely due to our ex-

tremely deep representations, we obtain a 28% relative im-

provement on the COCO object detection dataset. Deep

residual nets are foundations of our submissions to ILSVRC

& COCO 2015 competitions

1

, where we also won the 1st

places on the tasks of ImageNet detection, ImageNet local-

ization, COCO detection, and COCO segmentation.

1. Introduction

Deep convolutional neural networks [22, 21] have led

to a series of breakthroughs for image classification [21,

50, 40]. Deep networks naturally integrate low/mid/high-

level features [50] and classifiers in an end-to-end multi-

layer fashion, and the “levels” of features can be enriched

by the number of stacked layers (depth). Recent evidence

[41, 44] reveals that network depth is of crucial importance,

and the leading results [41, 44, 13, 16] on the challenging

ImageNet dataset [36] all exploit “very deep” [41] models,

with a depth of sixteen [41] to thirty [16]. Many other non-

trivial visual recognition tasks [8, 12, 7, 32, 27] have also

1

http://image-net.org/challenges/LSVRC/2015/ and

http://mscoco.org/dataset/#detections-challenge2015.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0

10

20

iter. (1e4)

training error (%)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0

10

20

iter. (1e4)

test error (%)

56-layer

20-layer

56-layer

20-layer

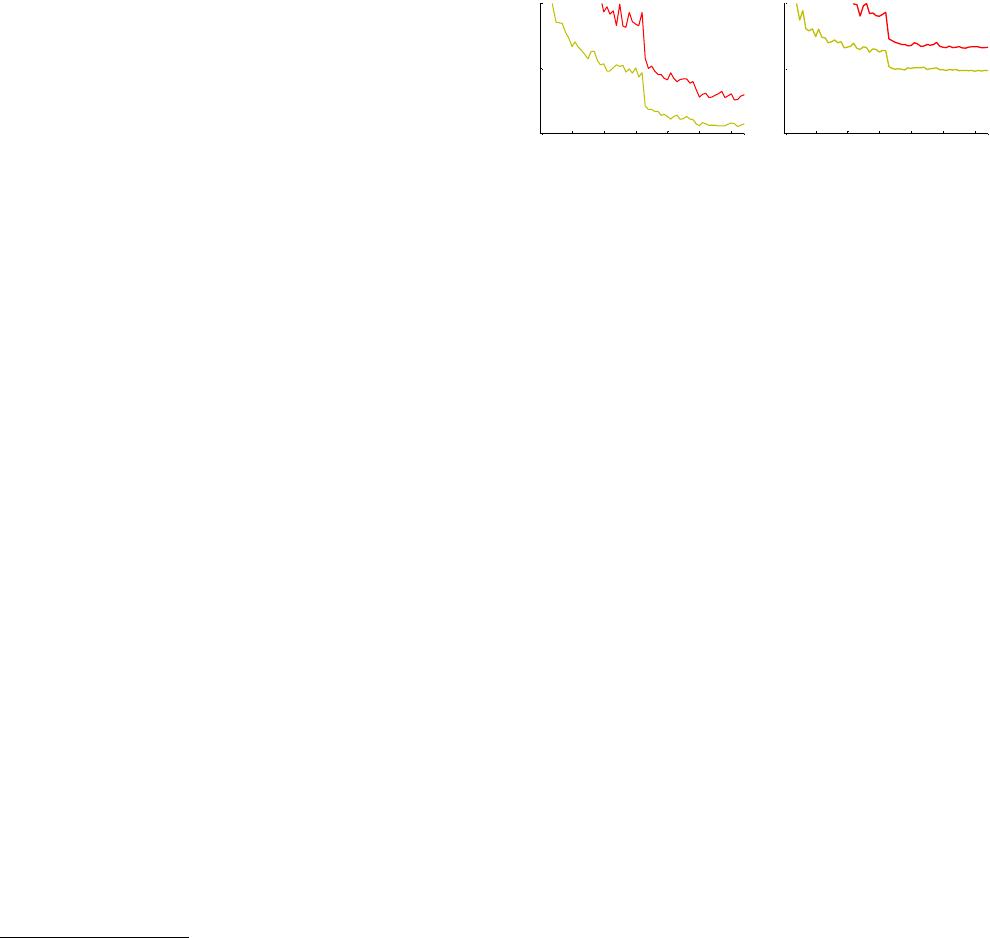

Figure 1. Training error (left) and test error (right) on CIFAR-10

with 20-layer and 56-layer “plain” networks. The deeper network

has higher training error, and thus test error. Similar phenomena

on ImageNet is presented in Fig. 4.

greatly benefited from very deep models.

Driven by the significance of depth, a question arises: Is

learning better networks as easy as stacking more layers?

An obstacle to answering this question was the notorious

problem of vanishing/exploding gradients [1, 9], which

hamper convergence from the beginning. This problem,

however, has been largely addressed by normalized initial-

ization [23, 9, 37, 13] and intermediate normalization layers

[16], which enable networks with tens of layers to start con-

verging for stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with back-

propagation [22].

When deeper networks are able to start converging, a

degradation problem has been exposed: with the network

depth increasing, accuracy gets saturated (which might be

unsurprising) and then degrades rapidly. Unexpectedly,

such degradation is not caused by overfitting, and adding

more layers to a suitably deep model leads to higher train-

ing error, as reported in [11, 42] and thoroughly verified by

our experiments. Fig. 1 shows a typical example.

The degradation (of training accuracy) indicates that not

all systems are similarly easy to optimize. Let us consider a

shallower architecture and its deeper counterpart that adds

more layers onto it. There exists a solution by construction

to the deeper model: the added layers are identity mapping,

and the other layers are copied from the learned shallower

model. The existence of this constructed solution indicates

that a deeper model should produce no higher training error

than its shallower counterpart. But experiments show that

our current solvers on hand are unable to find solutions that

1

arXiv:1512.03385v1 [cs.CV] 10 Dec 2015

identity

weight layer

weight layer

relu

relu

F(x)+x

x

F(x)

x

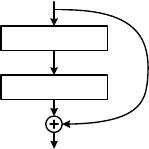

Figure 2. Residual learning: a building block.

are comparably good or better than the constructed solution

(or unable to do so in feasible time).

In this paper, we address the degradation problem by

introducing a deep residual learning framework. In-

stead of hoping each few stacked layers directly fit a

desired underlying mapping, we explicitly let these lay-

ers fit a residual mapping. Formally, denoting the desired

underlying mapping as H(x), we let the stacked nonlinear

layers fit another mapping of F(x) := H(x) − x. The orig-

inal mapping is recast into F(x)+x. We hypothesize that it

is easier to optimize the residual mapping than to optimize

the original, unreferenced mapping. To the extreme, if an

identity mapping were optimal, it would be easier to push

the residual to zero than to fit an identity mapping by a stack

of nonlinear layers.

The formulation of F(x) + x can be realized by feedfor-

ward neural networks with “shortcut connections” (Fig. 2).

Shortcut connections [2, 34, 49] are those skipping one or

more layers. In our case, the shortcut connections simply

perform identity mapping, and their outputs are added to

the outputs of the stacked layers (Fig. 2). Identity short-

cut connections add neither extra parameter nor computa-

tional complexity. The entire network can still be trained

end-to-end by SGD with backpropagation, and can be eas-

ily implemented using common libraries (e.g., Caffe [19])

without modifying the solvers.

We present comprehensive experiments on ImageNet

[36] to show the degradation problem and evaluate our

method. We show that: 1) Our extremely deep residual nets

are easy to optimize, but the counterpart “plain” nets (that

simply stack layers) exhibit higher training error when the

depth increases; 2) Our deep residual nets can easily enjoy

accuracy gains from greatly increased depth, producing re-

sults substantially better than previous networks.

Similar phenomena are also shown on the CIFAR-10 set

[20], suggesting that the optimization difficulties and the

effects of our method are not just akin to a particular dataset.

We present successfully trained models on this dataset with

over 100 layers, and explore models with over 1000 layers.

On the ImageNet classification dataset [36], we obtain

excellent results by extremely deep residual nets. Our 152-

layer residual net is the deepest network ever presented on

ImageNet, while still having lower complexity than VGG

nets [41]. Our ensemble has 3.57% top-5 error on the

ImageNet test set, and won the 1st place in the ILSVRC

2015 classification competition. The extremely deep rep-

resentations also have excellent generalization performance

on other recognition tasks, and lead us to further win the

1st places on: ImageNet detection, ImageNet localization,

COCO detection, and COCO segmentation in ILSVRC &

COCO 2015 competitions. This strong evidence shows that

the residual learning principle is generic, and we expect that

it is applicable in other vision and non-vision problems.

2. Related Work

Residual Representations. In image recognition, VLAD

[18] is a representation that encodes by the residual vectors

with respect to a dictionary, and Fisher Vector [30] can be

formulated as a probabilistic version [18] of VLAD. Both

of them are powerful shallow representations for image re-

trieval and classification [4, 48]. For vector quantization,

encoding residual vectors [17] is shown to be more effec-

tive than encoding original vectors.

In low-level vision and computer graphics, for solv-

ing Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), the widely used

Multigrid method [3] reformulates the system as subprob-

lems at multiple scales, where each subproblem is respon-

sible for the residual solution between a coarser and a finer

scale. An alternative to Multigrid is hierarchical basis pre-

conditioning [45, 46], which relies on variables that repre-

sent residual vectors between two scales. It has been shown

[3, 45, 46] that these solvers converge much faster than stan-

dard solvers that are unaware of the residual nature of the

solutions. These methods suggest that a good reformulation

or preconditioning can simplify the optimization.

Shortcut Connections. Practices and theories that lead to

shortcut connections [2, 34, 49] have been studied for a long

time. An early practice of training multi-layer perceptrons

(MLPs) is to add a linear layer connected from the network

input to the output [34, 49]. In [44, 24], a few interme-

diate layers are directly connected to auxiliary classifiers

for addressing vanishing/exploding gradients. The papers

of [39, 38, 31, 47] propose methods for centering layer re-

sponses, gradients, and propagated errors, implemented by

shortcut connections. In [44], an “inception” layer is com-

posed of a shortcut branch and a few deeper branches.

Concurrent with our work, “highway networks” [42, 43]

present shortcut connections with gating functions [15].

These gates are data-dependent and have parameters, in

contrast to our identity shortcuts that are parameter-free.

When a gated shortcut is “closed” (approaching zero), the

layers in highway networks represent non-residual func-

tions. On the contrary, our formulation always learns

residual functions; our identity shortcuts are never closed,

and all information is always passed through, with addi-

tional residual functions to be learned. In addition, high-

2

of 12

50墨值下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论