Consistently Estimating the Selectivity of Conjuncts of Predicates.pdf

50墨值下载

Consistently Estimating the Selectivity of

Conjuncts of Predicates

V. Markl

1

N. Megiddo

1

M. Kutsch

2

T.M. Tran

3

P. Haas

1

U. Srivastava

4

1

IBM Almaden Research Center

2

IBM Germany

3

IBM Silicon Valley Lab

4

Stanford University

{marklv, megiddo, peterh}@almaden.ibm.com, kutschm@de.ibm.com, minhtran@us.ibm.com, usriv@stanford.edu

Abstract

Cost-based query optimizers need to estimate the

selectivity of conjunctive predicates when com-

paring alternative query execution plans. To this

end, advanced optimizers use multivariate statis-

tics (MVS) to improve information about the

joint distribution of attribute values in a table.

The joint distribution for all columns is almost

always too large to store completely, and the re-

sulting use of partial distribution information

raises the possibility that multiple, non-equiva-

lent selectivity estimates may be available for a

given predicate. Current optimizers use ad hoc

methods to ensure that selectivities are estimated

in a consistent manner. These methods ignore

valuable information and tend to bias the opti-

mizer toward query plans for which the least in-

formation is available, often yielding poor re-

sults. In this paper we present a novel method for

consistent selectivity estimation based on the

principle of maximum entropy (ME). Our

method efficiently exploits all available infor-

mation and avoids the bias problem. In the ab-

sence of detailed knowledge, the ME approach

reduces to standard uniformity and independence

assumptions. Our implementation using a proto-

type version of DB2 UDB shows that ME im-

proves the optimizer’s cardinality estimates by

orders of magnitude, resulting in better plan

quality and significantly reduced query execution

times.

1. Introduction

Estimating the selectivity of predicates has always been a

challenging task for a query optimizer in a relational data-

base management system. A classic problem has been the

lack of detailed information about the joint frequency

distribution of attribute values in the table of interest. Per-

haps ironically, the additional information now available

to modern optimizers has in a certain sense made the se-

lectivity-estimation problem even harder.

Specifically, consider the problem of estimating the

selectivity s

1,2,…,n

of a conjunctive predicate of the form

p

1

∧ p

2

∧ … ∧ p

n

, where each p

i

is a simple predicate

(also called a Boolean Factor, or BF) of the form “column

op literal”. Here column is a column name, op is a

relational comparison operator such as “=”, “>”, or

“LIKE”, and literal is a literal in the domain of the col-

umn; some examples of simple predicates are ‘make =

“Honda”’ and ‘year > 1984’. By the selectivity of a predi-

cate p, we mean, as usual, the fraction of rows in the table

that satisfy p.

1

In older optimizers, statistics are

maintained on each individual column, so that the

individual selectivities s

1

, s

2

, …, s

n

of p

1

, p

2

, …, p

n

are

available. Such a query optimizer would then impose an

independence assumption and estimate the desired

selectivity as s

1,2,…,n

= s

1

* s

2

* … * s

n

. Such estimates

ignore correlations between attribute values, and

consequently can be wildly inaccurate, often

underestimating the true selectivity by orders of

magnitude and leading to a poor choice of query

execution plan (QEP).

Ideally, to overcome the problems caused by the inde-

pendence assumption, the optimizer should store the

multidimensional joint frequency distribution for all of the

columns in the database. In practice, the amount of

1

Note that without loss of generality each p

i

can also be a

disjunction of simple predicates or any other kind of predicate

(e.g., subquery, IN-list). For this work we only require that the

optimizer has some way to estimate the selectivity s

i

of p

i

.

Permission to copy without fee all or part of this material is

granted provided that the copies are not made or distributed

for direct commercial advantage, the VLDB copyright notice

and the title of the publication and its date appear, and notice

is given that copying is by permission of the Very Large Data

Base Endowment. To copy otherwise, or to republish, re-

quires a fee and/or special permission from the Endowment.

Proceedings of the 31st VLDB Conference,

Trondheim, Norway, 2005.

373

storage required for the full distribution is exponentially

large, making this approach infeasible. Researchers

therefore have proposed storage of selected multivariate

statistics (MVS) that summarize important partial

information about the joint distribution. Proposals have

ranged from multidimensional histograms [PI97] on

selected columns to other, simpler forms of column-group

statistics [IMH+04]. Thus, for predicates p

1

, p

2

, …, p

n

, the

optimizer typically has access to the individual

selectivities s

1

, s

2

, …, s

n

as well as a limited collection of

joint selectivities, such as s

1,2

, s

3,5

, and s

2,3,4

. The

independence assumption is then used to “fill in the gaps”

in the incomplete information, e.g., we can estimate the

unknown selectivity s

1,2,3

by s

1,2

* s

3

.

A new and serious problem now arises, however.

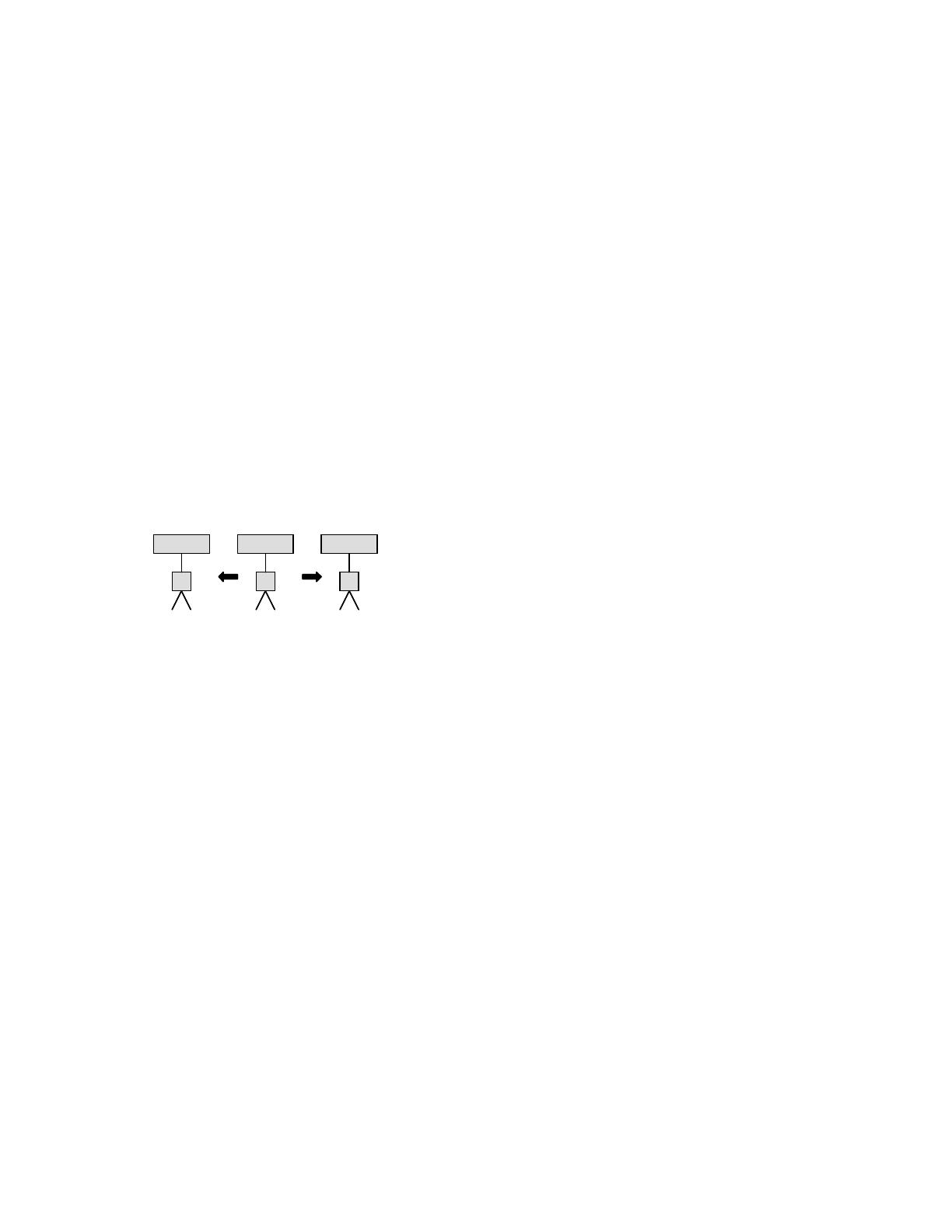

There may be multiple, non-equivalent ways of estimating

the selectivity for a given predicate. Figure 1, for exam-

ple, shows possible QEPs for a query consisting of the

conjunctive predicate p

1

∧ p

2

∧ p

3

. The QEP in Figure

1(a) uses an index-ANDing operation (∧) to apply p

1

∧ p

2

and afterwards applies predicate p

3

by a FETCH operator,

which retrieves rows from a base table according to the

row identifiers returned from the index-ANDing operator.

p

1

p

3

∧

FETCH p

2

s

1,3

s

1,3

* s

2

p

1

p

2

∧

FETCH p

3

s

1,2

s

1,2

* s

3

p

1

p

3

∧

FETCH p

2

s

1

* s

3

s

1,2

* s

3

(b) (a) (c)

≠

=

p

1

p

3

∧

FETCH p

2

s

1,3

s

1,3

* s

2

p

1

p

2

∧

FETCH p

3

s

1,2

s

1,2

* s

3

p

1

p

3

∧

FETCH p

2

s

1

* s

3

s

1,2

* s

3

(b) (a) (c)

≠

=

Figure 1: QEPs and Selectivity Estimation

Suppose that the optimizer knows the selectivities s

1

,

s

2

, s

3

of the BFs p

1

, p

2

, p

3

. Also suppose that it knows

about a correlation between p

1

and p

2

via knowledge of

the selectivity s

1,2

of p

1

∧ p

2

. Using independence, the

optimizer might then estimate the selectivity of p

1

∧ p

2

∧

p

3

as s

a

1,2,3

= s

1,2

* s

3

.

Figure 1(b) shows an alternative QEP that first applies

p

1

∧ p

3

and then applies p

2

. If the optimizer also knows

the selectivity s

1,3

of p

1

∧ p

3

, use of the independence

assumption might yield a selectivity estimate s

b

1,2,3

= s

1,3

*

s

2

. However, this would result in an inconsistency if, as is

likely, s

a

1,2,3

≠ s

b

1,2,3

. There are potentially other choices,

such as s

1

* s

2

* s

3

or, if s

2,3

is known, s

1,2

*s

2,3

/s

2

; the latter

estimate amounts to a conditional independence assump-

tion. Any choice of estimate will be arbitrary, since there

is no supporting knowledge to justify ignoring a

correlation or assuming conditional independence; such a

choice will then arbitrarily bias the optimizer toward

choosing one plan over the other. Even worse, if the

optimizer does not use the same choice of estimate every

time that it is required, then different plans will be costed

inconsistently, leading to “apples and oranges”

comparisons and unreliable plan choices

Assuming that the QEP in Figure 1(a) is the first to be

evaluated, a modern optimizer would avoid the foregoing

consistency problem by recording the fact that s

1,2

was

applied and then avoiding future application of any other

MVS that contain either p

1

or p

2

, but not both. In our

example, the selectivities for the QEP in Figure 1(c)

would be used and the ones in Figure 1(b) would not. The

optimizer would therefore compute the selectivity of p

1

∧

p

3

to be s

1

* s

3

using independence, instead of using the

MVS s

1,3

. Thus the selectivity s

1,2,3

would be estimated in

a manner consistent with Figure 1(a). Note that, when

evaluating the QEP in Figure 1(a), the optimizer used the

estimate s

a

1,2,3

= s

1,2

* s

3

rather than s

1

* s

2

* s

3

, since, in-

tuitively, the former estimate better exploits the available

correlation information. In general, there may be many

possible choices; the complicated (ad hoc) decision

algorithm used by DB2 UDB is described in more detail

in the Appendix.

Although the ad hoc method described above ensures

consistency, it ignores valuable knowledge, e.g., of the

correlation between p

1

and p

3.

Moreover, this method

complicates the logic of the optimizer, because

cumbersome bookkeeping is required to keep track of

how an estimate was derived initially and to ensure that it

will always be computed in the same way when costing

other plans. Even worse, ignoring the known correlation

between p

1

and p

3

also introduces bias towards certain

QEPs: if, as is often the case with correlation, s

1,3

>> s

1

*

s

3

, and s

1,2

>> s

1

* s

2

, and if s

1,2

and s

1,3

have comparable

values, then the optimizer will be biased towards the plan

in Figure 1(c), even though the plan in Figure 1(a) might

be cheaper, i.e., the optimizer thinks that the plan in

Figure 1(c) will produce fewer rows during index-

ANDing, but this might not actually be the case. In

general, an optimizer will often be drawn towards those

QEPs about which it knows the least, because use of the

independence assumption makes these plans seem

cheaper due to underestimation. We call this problem

“fleeing from knowledge to ignorance”.

In this paper, we provide a novel method for estimat-

ing the selectivity of a conjunctive predicate; the method

exploits and combines all of the available MVS in a prin-

cipled, consistent, and unbiased manner. Our technique

rests on the principle of maximum entropy (ME) [GS85],

which is a mathematical embodiment of Occam’s Razor

and provides the “simplest” possible selectivity estimate

that is consistent with all of the available information. (In

the absence of detailed knowledge, the ME approach re-

duces to standard uniformity and independence assump-

tions.) Our new approach avoids the problems of incon-

sistent QEP comparisons and the flight from knowledge

to ignorance.

We emphasize that, unlike DB2’s ad hoc method or

the method proposed in [BC02] (which tries to choose the

“best” of the available MVS for estimating a selectivity)

the ME method is the first to exploit all of the available

MVS and actually refine the optimizer’s cardinality model

374

of 12

50墨值下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论