2006CVPR最佳论文-在透视场景中放置物体.pdf

50墨值下载

Putting Objects in Perspective

Derek Hoiem Alexei A. Efros Martial Hebert

Carnegie Mellon University, Robotics Institute

{dhoiem,efros,hebert}@cs.cmu.edu

Abstract

Image understanding requires not only individually esti-

mating elements of the visual world but also capturing the

interplay among them. In this paper, we provide a frame-

work for placing local object detection in the context of the

overall 3D scene by modeling the interdependence of ob-

jects, surface orientations, and camera viewpoint.

Most object detection methods consider all scales and

locations in the image as equally likely. We show that with

probabilistic estimates of 3D geometry, both in terms of

surfaces and world coordinates, we can put objects into

perspective and model the scale and location variance in

the image. Our approach reflects the cyclical nature of the

problem by allowing probabilistic object hypotheses to re-

fine geometry and vice-versa. Our framework allows pain-

less substitution of almost any object detector and is easily

extended to include other aspects of image understanding.

Our results confirm the benefits of our integrated approach.

1. Introduction

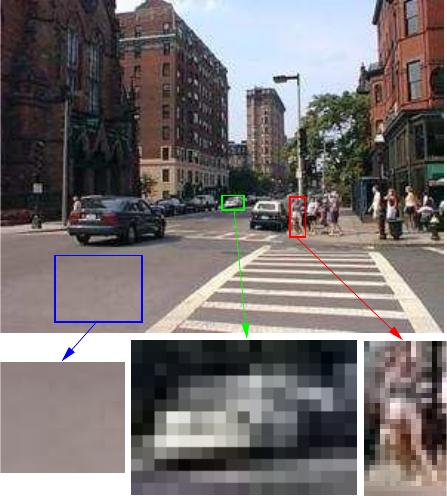

Consider the street scene depicted on Figure 1. Most

people will have little trouble seeing that the green box

in the middle contains a car. This is despite the fact that,

shown in isolation, these same pixels can just as easily be in-

terpreted as a person’s shoulder, a mouse, a stack of books,

a balcony, or a million other things! Yet, when we look at

the entire scene, all ambiguity is resolved – the car is un-

mistakably a car. How do we do this?

There is strong psychophysical evidence (e.g. [3, 25])

that context plays a crucial role in scene understanding. In

our example, the car-like blob is recognized as a car be-

cause: 1) it’s sitting on the road, and 2) it’s the “right”

size, relative to other objects in the scene (cars, buildings,

pedestrians, etc). Of course, the trouble is that everything is

tightly interconnected – a visual object that uses others as its

context will, in turn, be used as context by these other ob-

jects. We recognize a car because it’s on the road. But how

do we recognize a road? – because there are cars! How does

one attack this chicken-and-egg problem? What is the right

framework for connecting all these pieces of the recognition

puzzle in a coherent and tractable manner?

In this paper we will propose a unified approach for mod-

eling the contextual symbiosis between three crucial ele-

Figure 1. General object recognition cannot be solved locally, but

requires the interpretation of the entire image. In the above image,

it’s virtually impossible to recognize the car, the person and the

road in isolation, but taken together they form a coherent visual

story. Our paper tells this story.

ments required for scene understanding: low-level object

detectors, rough 3D scene geometry, and approximate cam-

era position/orientation. Our main insight is to model the

contextual relationships between the visual elements, not in

the 2D image plane where they have been projected by the

camera, but within the 3D world where they actually re-

side. Perspective projection obscures the relationships that

are present in the actual scene: a nearby car will appear

much bigger than a car far away, even though in reality they

are the same height. We “undo” the perspective projection

and analyze the objects in the space of the 3D scene.

1.1. Background

In its early days, computer vision had but a single grand

goal: to provide a complete semantic interpretation of an

input image by reasoning about the 3D scene that gener-

ated it. Indeed, by the late 1970s there were several im-

age understanding systems being developed, including such

2.2<y

c

<2.8

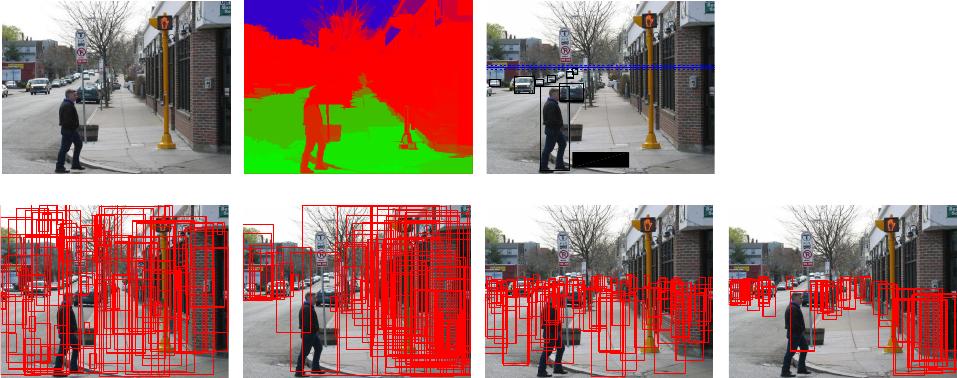

(a) input image (c) surface orientation estimate (e) P(viewpoint | objects)

(b) P(person) = uniform (d) P(person | geometry) (f) P(person | viewpoint) (g) P(person |viewpoint,geometry)

Figure 2. Watch for pedestrians! In (b,d,f,g), we show 100 boxes sampled according to the available information. Given an input image (a),

a local object detector will expect to find a pedestrian at any location/scale (b). However, given an estimate of rough surface orientations

(c), we can better predict where a pedestrian is likely to be (d). We can estimate the camera viewpoint (e) from a few known objects in

the image. Conversely, knowing the camera viewpoint can help in predict the likely scale of a pedestrian (f). The combined evidence from

surface geometry and camera viewpoint provides a powerful predictor of where a pedestrian might be (g), before we even run a pedestrian

detector! Red, green, and blue channels of (c) indicate confidence in vertical, ground, and sky, respectively. Best viewed in color.

pioneering work as Brooks’ ACRONYM [4], Hanson and

Riseman’s VISIONS [9], Ohta and Kanade’s outdoor scene

understanding system [19], Barrow and Tenenbaum’s in-

trinsic images [2], etc. For example, VISIONS was an ex-

tremely ambitious system that analyzed a scene on many

interrelated levels including segments, 3D surfaces and vol-

umes, objects, and scene categories. However, because of

the heavy use of heuristics, none of these early systems were

particularly successful, which led people to doubt the very

goal of complete image understanding.

We believe that the vision pioneers were simply ahead

of their time. They had no choice but to rely on heuris-

tics because they lacked the computational resources to

learn the relationships governing the structure of our visual

world. The advancement of learning methods in the last

decade brings renewed hope for a complete image under-

standing solution. However, the currently popular learning

approaches are based on looking at small image windows at

all locations and scales to find specific objects. This works

wonderfully for face detection [23, 29] (since the inside of

a face is much more important than the boundary) but is

quite unreliable for other types of objects, such as cars and

pedestrians, especially at the smaller scales.

As a result, several researchers have recently begun to

consider the use of contextual information for object de-

tection. The main focus has been on modeling direct re-

lationships between objects and other objects [15, 18], re-

gions [10, 16, 28] or scene categories [18, 24], all within

the 2D image. Going beyond the 2D image plane, Hoiem et

al. [11] propose a mechanism for estimating rough 3D scene

geometry from a single image and use this information as

additional features to improve object detection. From low-

level image cues, Torralba and Oliva [26] get a sense of the

viewpoint and mean scene depth, which provides a useful

prior for object detection [27]. Forsyth et al. [7] describe

a method for geometric consistency of object hypotheses in

simple scenes using hard algebraic constraints. Others have

also modeled the relationship between the camera parame-

ters and objects, requiring either a well-calibrated camera

(e.g. [12]), a stationary surveillance camera (e.g. [14]), or

both [8].

In this work, we draw on several of the previous tech-

niques: local object detection (based on Murphy et al. [18]),

3D scene geometry estimation [11], and camera viewpoint

estimation. Our contribution is a statistical framework that

allows simultaneous inference of object identities, surface

orientations, and camera viewpoint using a single image

taken from an uncalibrated camera.

1.2. Overview

To evaluate our approach, we have chosen a very chal-

lenging dataset of outdoor images [22] that contain cars and

people, often partly occluded, over an extremely wide range

of scales and in accidental poses (unlike, for example, the

framed photographs in Corel or CalTech datasets). Our goal

is to demonstrate that substantial improvement over stan-

dard low-level detectors can be obtained by reasoning about

the underlying 3D scene structure.

One way to think about what we are trying to achieve

is to consider the likely places in an image where an ob-

of 9

50墨值下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论