学习智能对话框用于边界框注释.pdf

50墨值下载

Learning Intelligent Dialogs for Bounding Box Annotation

Ksenia Konyushkova

CVLab, EPFL

ksenia.konyushkova@epfl.ch

∗

Jasper Uijlings

Google AI Perception

jrru@google.com

Christoph H. Lampert

IST Austria

chl@ist.ac.at

Vittorio Ferrari

Google AI Perception

vittoferrari@google.com

Abstract

We introduce Intelligent Annotation Dialogs for bounding

box annotation. We train an agent to automatically choose

a sequence of actions for a human annotator to produce

a bounding box in a minimal amount of time. Specifically,

we consider two actions: box verification [

34

], where the

annotator verifies a box generated by an object detector, and

manual box drawing. We explore two kinds of agents, one

based on predicting the probability that a box will be posi-

tively verified, and the other based on reinforcement learning.

We demonstrate that (1) our agents are able to learn efficient

annotation strategies in several scenarios, automatically

adapting to the image difficulty, the desired quality of the

boxes, and the detector strength; (2) in all scenarios the re-

sulting annotation dialogs speed up annotation compared to

manual box drawing alone and box verification alone, while

also outperforming any fixed combination of verification and

drawing in most scenarios; (3) in a realistic scenario where

the detector is iteratively re-trained, our agents evolve a

series of strategies that reflect the shifting trade-off between

verification and drawing as the detector grows stronger.

1. Introduction

Many recent advances in computer vision rely on super-

vised machine learning techniques that are known to crave

for huge amounts of training data. Object detection is no

exception as state-of-the-art methods require a large number

of images with annotated bounding boxes around objects.

However, drawing high quality bounding boxes is expensive:

The official protocol used to annotate ILSVRC [

38

] takes

about 30 seconds per box [

43

]. To reduce this cost, recent

works explore cheaper forms of human supervision such as

image-level labels [

6

,

21

,

53

], box verification series [

34

],

point annotations [27, 33], and eye-tracking [31].

Among these forms, the recent work on box verification

series [

34

] stands out as it demonstrated to deliver high

quality detectors at low cost. The scheme starts from a given

∗

This work was done during an internship at Google AI Perception

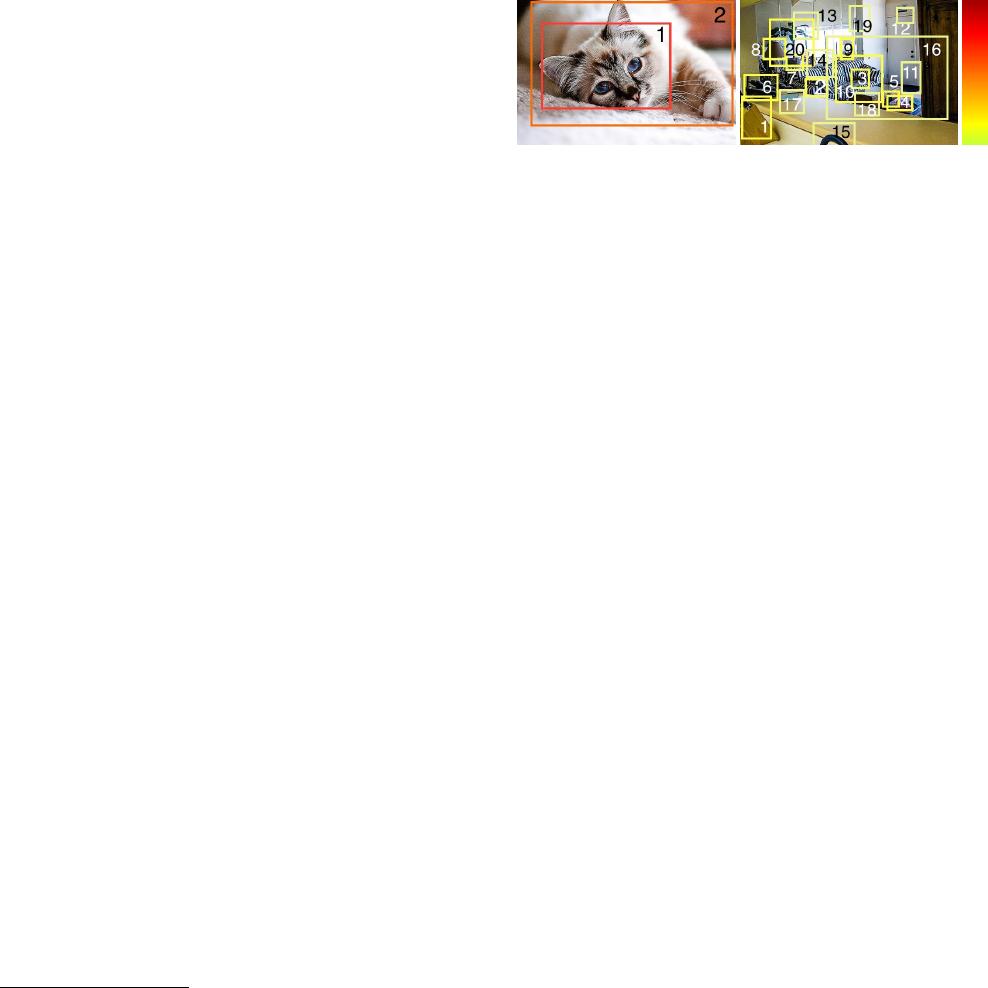

Figure 1: Left: an image with a target class cat. The weak

detector identified two box proposals with high scores. The

best strategy in this case is to do a series of box verifications.

Right: an image with a target class potted plant. The weak

detector identified many box proposals with low scores. The

best strategy is to draw a box.

weak detector, typically trained on image labels only, and

uses it to localize objects in the images. For each image, the

annotator is asked to verify whether the box produced by

the algorithm covers an object tightly enough. If not, the

process iterates: the algorithm proposes another box and the

annotator verifies it.

The success of box verification series depends on a variety

of factors. For example, large objects on homogeneous back-

grounds are likely to be found early in the series, and hence

require little annotation time (Fig. 1, left). However, small

objects in crowded scenes might require many iterations, or

could even not be found at all (Fig. 1, right). Furthermore,

the stronger the detector is, the more likely it is to correctly

localize new objects, and to do so early in the series. Finally,

the higher the desired box quality (i.e. how tight they should

be), the lower the rate of positively verified boxes. This

causes longer series, costing more annotation time. There-

fore, in some situations manual box drawing [

32

,

43

] is

preferable. While more expensive than one verification, it

always produces a box annotation. When an annotation

episode consists of many verifications, its duration can be

longer than the time to draw a box, depending on the relative

costs of the two actions. Thus, different forms of annotation

are more efficient in different situations.

In this paper we introduce Intelligent Annotation Dialogs

(IAD) for bounding box annotation. Given an image, detec-

tor, and target class to be annotated, the aim of IAD is to

automatically choose the sequence of annotation actions that

1

arXiv:1712.08087v3 [cs.CV] 20 Nov 2018

results in producing a bounding box in the least amount of

time. We train an IAD agent to select the type of action based

on previous experience in annotating images. Our method au-

tomatically adapts to the difficulty of the image, the strength

of the detector, the desired quality of the boxes, and other fac-

tors. This is achieved by modeling the episode duration as a

function of problem properties. We consider two alternative

ways to do this, either a) by predicting whether a proposed

box will be positively or negatively verified (Sec. 4.1), or

b) by directly predicting the episode duration (Sec. 4.2).

We evaluate IAD by annotating bounding boxes in the

PASCAL VOC 2007 dataset [

15

] in several scenarios:

a) with various desired quality levels; b) with detectors of

varying strength; and c) with two ways to draw bounding

boxes, including a recent method which only takes 7s per

box [

32

]. In all scenarios our experiments demonstrate that

thanks to its adaptive behavior IAD speeds up box annotation

compared to manual box drawing alone, or box verification

series alone. Moreover, it outperforms any fixed combina-

tion of them in most scenarios. Finally, we demonstrate

that IAD learns useful strategies in a complex realistic sce-

nario where the detector is continuously improved with the

growing amount of the training data. Our IAD code is made

publicly available

1

.

2. Related work

Drawing bounding boxes

Fully supervised object detec-

tors are trained on data with manually annotated bounding

boxes, which is costly. The reference box drawing inter-

face [

43

] used to annotate ILSVRC [

38

] requires 25.5s for

drawing one box. Recently, a more efficient interface re-

duces costs to 7.0s without compromising on quality [

32

].

We consider both interfaces in this paper.

Training object detectors from image-level labels

Weakly Supervised Object Localization (WSOL) [

6

,

13

,

14

,

16

,

21

,

53

] methods train object detectors from images la-

beled only as containing certain object classes, but without

bounding boxes. This avoids the cost of box annotation,

but leads to considerably weaker detectors than their fully

supervised counterparts [

6

,

16

,

21

,

53

]. To produce better

object detectors, extra human annotation is required.

Other forms of weak supervision

Several works aim to

reduce annotation cost of manual drawing by using ap-

proximate forms of annotation. Eye-tracking is used for

training object detectors [

31

] and for action recognition in

videos [

26

]. Point-clicks are used to derive bounding box

annotations in images [

33

] and video [

27

], and to train se-

mantic segmentation models [

2

,

3

,

50

]. Other works train

semantic segmentation models using scribbles [25, 51].

In this paper we build on box verification series [

34

],

where boxes are iteratively proposed by an object detector

1

https://github.com/google/intelligent_annotation_dialogs

and verified by a human annotator. Experiments show that

humans can perform box verification reliably (Fig.

6

of [

34

]).

Besides, the Open Images dataset [

23

] contains

2.5

Million

boxes annotated in this manner, demonstrating it can be done

at scale.

Interactive annotation

Several works use human-

machine collaboration to efficiently produce anno-

tations. These works address interactive segmenta-

tion [

8

,

37

,

12

,

18

,

17

,

30

], attribute-based fine-grained

image classification [

10

,

35

,

7

,

49

], and interactive video

annotation [

48

]. Branson et al. [

9

] transform different

types of location information (e.g. parts, bounding boxes,

segmentations) into each other with corrections from an

annotator. These works follow a predefined annotation pro-

tocol, whereas we explore algorithms that can automatically

select questions, adapting to the input image, the desired

quality of the annotation, and other factors.

The closest work [

39

] to ours proposes human-machine

collaboration for bounding box annotation. Given a reper-

toire of questions, the problem is modeled with a Markov

decision process. Our work differs in several respects.

(1) While Russakovsky et al. [

39

] optimizes the expected

precision of annotations over the whole dataset, our method

delivers quality guarantees on each individual box. (2) Our

approach of Sec 4.1 is mediated by predicting the probability

of a box to be accepted by an annotator. Based on this, we

provide a provably optimal strategy which minimizes the

expected annotation time. (3) Our reinforcement learning

approach of Sec. 4.2 learns a direct mapping from from

measurable properties to annotation time, while avoiding

any explicit modelling of the task. (4) Finally, we address a

scenario where the detector is iteratively updated (Sec. 5.3),

as opposed to keeping it fixed.

Active learning (AL)

In active learning the goal is to train

a model while asking human annotations for unlabeled ex-

amples which are expected to improve the model accuracy

the most. It is used in computer vision to train whole-image

classifiers [

20

,

22

], object class detectors [

47

,

52

], and se-

mantic segmentation [

41

,

45

,

46

]. While the goal of AL is

to select a subset of the data to be annotated, this paper aims

at minimizing the time to annotate each of the examples.

Reinforcement learning

Reinforcement learning (RL)

traditionally aims at learning policies that allow autonomous

agents to act in interactive environments. Reinforcement

learning has a long tradition e.g. in robotics [

1

,

28

,

24

]. In

computer vision, it has mainly been used for active vision

tasks [

11

,

4

,

19

], such as learning a policy for the spatial

exploration of large images or panoramic images. Our use

of RL differs from this, as we learn a policy for image anno-

tation, not for image analysis. The learned policy enables

the system to dynamically choose the annotation mechanism

by which to interact with the user.

of 11

50墨值下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论