推断来自阴影中的光场.pdf

50墨值下载

Inferring Light Fields from Shadows

Manel Baradad

1

Vickie Ye

1

Adam B. Yedidia

1

Fr

´

edo Durand

1

William T. Freeman

1,2

Gregory W. Wornell

1

Antonio Torralba

1

1

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

2

Google Research

{mbaradad,vye16,adamy,fredo,billf,gww}@mit.edu, torralba@csail.mit.edu

Abstract

We present a method for inferring a 4D light field of a

hidden scene from 2D shadows cast by a known occluder

on a diffuse wall. We do this by determining how light

naturally reflected off surfaces in the hidden scene interacts

with the occluder. By modeling the light transport as a

linear system, and incorporating prior knowledge about

light field structures, we can invert the system to recover

the hidden scene. We demonstrate results of our inference

method across simulations and experiments with different

types of occluders. For instance, using the shadow cast by

a real house plant, we are able to recover low resolution

light fields with different levels of texture and parallax

complexity. We provide two experimental results: a human

subject and two planar elements at different depths.

1. Introduction

Imagine you are peering into a room through an open

doorway, and all you can see is a white wall and an object

placed just in front of it. Although you cannot see the rest

of the room directly, the object is casting complex shadows

on the wall (see Fig. 1). What information can be deduced

from the patterns these shadows make? Is recovering a 2D

picture of the room possible? What about depth recovery?

The problem of imaging scenes that are not within direct

line of sight has a wide range of applications, including

search-and-rescue, anti-terrorism and transportation [2].

However, this problem is very challenging. Previous

approaches to non-line-of-sight (NLoS) imaging have used

time-of-flight (ToF) cameras or shadows cast by ambient

light to count objects in the hidden scene [28], or to

reconstruct approximate low-dimensional images [3, 23].

In this paper, we attempt a far more ambitious class of

reconstructions: estimating the 4D light field produced by

what remains hidden. The recovered light field would allow

us to view the hidden scene from multiple perspectives and

Figure 1: Example scenario. An observer peers partially

into a room, and she is only able to see two things: a plant

and the shadow it casts on the wall. If the observer can fully

characterize the geometry of the plant, what can she learn

about the rest of the room by analyzing the shadow?

thereby recover parallax information that can tell us about

the hidden scene’s geometry.

Previous NLoS imaging methods that rely on secondary

reflections from a naturally illuminated hidden scene use

the known imaging conditions to approximate a transfer

matrix—a linear relationship between all elements in the

scene to observations on the visible reflector. They

then invert this transfer matrix while simultaneously

incorporating prior knowledge about likely scene structure,

yielding a transformation that takes these observations as

input and returns a reconstruction of the scene.

Our approach is also modeled on these principles, but

prior knowledge plays an even more important role. An

image of the white wall only provides a 2D array of

observations. If we are going to reconstruct a 4D array

of light-field samples from a vastly smaller number of

observations, we must rely much more heavily on our

1

prior distribution over light fields to obtain meaningful

reconstructions. In particular, we can exploit the fact that

elements of real scenes have spectra that are concentrated at

low frequencies [4]. This allows us to reduce the effective

dimensionality of the resulting problem to the point of

tractability.

Our work also suggests that complex occluders can help

reveal disparity information about a scene, more so than

simple ones. This means that a commonplace houseplant

that has a complex structure may be a better computational

light field camera than a simpler pinspeck occluder. This

is consistent with conventional wisdom about occlusions

derived from past work in coded-aperture imaging, such as

in [15].

Even with these insights, our approach relies on having

an accurate estimate of the occluder’s geometry and direct

illumination over what remains hidden. Nevertheless, we

think that our approach provides a strong template for future

progress in NLoS imaging and compelling evidence that the

world around us is covered with subtle, but very rich, visual

information.

2. Background

2.1. NLoS Imaging

Non-line-of-sight (NLoS) imaging is the study of how to

infer information about objects that are not directly visible.

Many approaches to NLoS imaging involve a combination

of active laser illumination and ToF cameras [13, 19, 29].

These methods, called active methods, work by illuminating

a point on the visible region that projects light into the

hidden scene. Then, structure in the scene can be inferred

from the time it takes for that light to return [12, 20, 22, 24].

These methods have been used to count hidden people [28],

or to infer location, size and motion of objects [9, 11, 18].

Other recent approaches, called passive methods, rely

on ambient light from the hidden scene or elsewhere

for inference. These approaches range from using

naturally-occurring pinholes or pinspecks [7, 23] to using

edges [3] to resolve the scene. Our work can be thought

of as the extension of these same principles to arbitrary

known occluders. To our knowledge, this work is the

first to demonstrate reconstructions of 2D images from

arbitrary known occluders in an NLoS setting, let alone

reconstructions of 4D light fields.

2.2. Light field reconstructions

There has been ample prior work on inference of the

full light field function for directly-visible scenes. This

problem is addressed in [6], [8], [14], [21], [26], [27],

among others. Notably, the work of [21] estimates a full 4D

light field from a single 2D image of the scene. However,

this learning-based method is trained on very constrained

Observed

pixels

=

...

Transfer matrix

Unoccluded

light �eld

D

x

u

l(x, u)

Hidden scene

Scene plane

Occluder

Observation plane

a)

b)

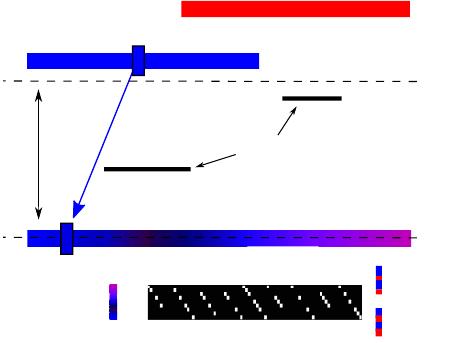

Figure 2: a) Simplified 2D scenario, depicting all

the elements of the scene (occluder, hidden scene and

observation plane) and the parametrization planes for the

light field (dashed lines). (b) Discretized version of the

scenario, with the light field and the observation encoded

as the discrete vectors x and y, respectively. The transfer

matrix is a sparse, row-deficient matrix that encodes the

occlusion and reflection in the system.

domain-specific data and is unable to accurately extend to

novel images. This past work, particularly [14], heavily

informed our choice of prior over light fields, which we

discuss at length in Sec. 5.

3. Overview

In order to reconstruct light fields using secondary

reflections from the scene, our imaging method has two

main components. The first is a linear forward model

that computes observations from light fields, i.e. a transfer

matrix A, that has many columns but is sparse. The transfer

matrix for an arbitrary scene is depicted schematically in

Fig. 2.

The second is a prior distribution on light fields that

allows reducing the effective dimensionality of the inverse

problem, turning this ill-posed problem into one that is

well-posed and computationally feasible. This strategy is

better than other methods for reducing the dimensionality

of the inverse problem (for example, naively downsampling

the forward model and inverting). Light field sampling

theory [5] and novel light field priors [14] inform how we

reduce the dimensionality of the inverse problem given mild

assumptions of the elements that produce the light field to

be recovered.

In Section 4, we describe our model for how light

propagates in the scene as well as our mathematical

representations for each of its components. These choices

of 10

50墨值下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论