In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm

免费下载

In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm

(Extended Version)

Diego Ongaro and John Oust erhou t

Stanford University

Abstract

Raft is a consen sus algorithm for managing a replicated

log. It produces a result equivalent to (multi-)Paxos, and

it is as efficient as Paxos, but its structur e is different

from Paxos; this makes Raft more understandab le than

Paxos and also provides a better foundation for build-

ing practical system s. In order to enhance understandabil-

ity, Raft separates the key elements of consensus, such as

leader election, log replication, and safety, and it enforce s

a stronger degree of coherency to reduce the number of

states that must be considered. Results from a user study

demonstra te that Raft is easier for students to learn than

Paxos. Raft also includes a new m e chanism for changing

the cluster membership, which uses overlapping majori-

ties to gua rantee safety.

1 Introduction

Consensus algorithm s allow a collection of machin es

to work as a coheren t group that ca n survive the fail-

ures o f some of its members. Because of this, they play a

key role in building reliable large-scale software systems.

Paxos [15, 16] has dominated the discussion of consen-

sus algorithms over the last decade: most implementations

of consensus are based on Paxos or influenced by it, and

Paxos has become the primary vehicle used to teach stu-

dents about c onsensus.

Unfortu nately, Paxos is quite difficult to understand, in

spite of numerous attempts to make it more approachable.

Furthermore, its architecture requires complex chan ges

to support practical systems. As a result, both system

builders and students struggle with Paxos.

After struggling with Paxos ourselves, we set out to

find a new consensus algorithm that could provide a bet-

ter foundatio n for system building and education. Our ap-

proach was unusua l in that our primary goal was under-

standability: could we define a consensus algorithm for

practical systems and describe it in a way that is signifi-

cantly easier to learn than Paxos? Furtherm ore, we wanted

the algorithm to facilitate the development of intuitions

that are essential for system builders. It was important not

just for the algorithm to work, but for it to be obvious why

it works.

The result of this work is a consensus algorithm called

Raft. In designing Raft we applied specific techniques to

improve understand ability, including de composition (Raft

separates leader election, log rep lica tion, and safety) and

This tech report is an extended version of [32]; additional material is

noted with a gray bar in the margin. Published May 20, 2014.

state space reduction (relative to Paxos, Raft reduces the

degree of nondeterminism and th e ways servers can be in-

consistent with each othe r). A user study with 43 students

at two universities shows that Raft is significan tly easier

to understan d than Paxos: after learning both algorithms,

33 of these students were able to answer questions about

Raft better than questions about Paxos.

Raft is similar in m any ways to existing consensus al-

gorithms (most notably, Oki and Liskov’s Viewstamped

Replication [29, 22]), but it has several novel fea tures:

• Strong leader: Raft u ses a stronger form of leader-

ship than other consensus algorithms. For example,

log entries only flow fr om the leader to other servers.

This simplifies the management of the replicated log

and makes Raft easier to understand.

• Leader election: Raft uses randomized timers to

elect leaders. This adds only a small amount of

mechanism to the heartbeats already required for any

consensus algorithm, while resolving conflicts sim-

ply and rapidly.

• Membership changes: Raft’s mechanism for

changin g the set of servers in the cluster uses a new

joint consensus approach where the majorities of

two different configurations overlap during transi-

tions. This allows the cluster to continue opera ting

normally du ring configuration changes.

We believe that Raft is superior to Paxos and othe r con-

sensus algorithms, both for educatio nal purposes and as a

foundation for implementation. It is simpler and more un-

derstandable than other algorithms; it is described com-

pletely enough to m eet the needs of a practical system;

it has several open-source implementations and is used

by several companies; its saf ety properties have bee n for-

mally specified and proven; and its efficiency is compara-

ble to other algorithms.

The remainder of the paper intr oduces the replicated

state machine p roblem (Section 2), discusses the strength s

and weaknesses of Paxos (Section 3), describes our gen-

eral approach to u nderstandability (Section 4), presents

the Raft co nsensus algorithm (Sections 5–8), evaluates

Raft (Section 9), and discusses related work (Section 10).

2 Replicated state machines

Consensus algorithms typically arise in the context of

replicated state machines [ 37]. In this approach, state m a-

chines on a collection of servers compute identical copies

of the same state an d can continue operating even if some

of the servers are down. Replicated state machines are

1

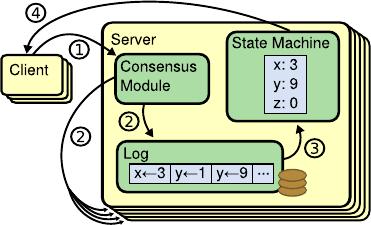

Figure 1: Replicated state machine architecture. The con-

sensus al gorithm manages a replicated log containing state

machine commands f rom clients. The state machines process

identical sequences of commands from the logs, so they pro-

duce the same outputs.

used to solve a variety of fault tolerance problems in dis-

tributed systems. For example, large-scale systems that

have a single cluster leader, such as GFS [8], HDFS [38],

and RAMCloud [33], typically use a separate replicated

state machine to manage leader election and stor e config-

uration information that must survive leader crashes. Ex-

amples of replicated state machines include Chubby [2]

and ZooKeeper [11].

Replicated state machines are typically implemented

using a replicated log, as shown in Figure 1. Each server

stores a log containing a series of comma nds, which its

state ma chine executes in order. Each log contains the

same comma nds in the same order, so each state ma-

chine processes the same seq uence of commands. Since

the state machines are determin istic, each computes the

same state and the same sequen c e of outputs.

Keeping the replicated log consistent is the job of the

consensus algorithm. The consensus modu le on a server

receives commands from clients and adds them to its log.

It communicate s with the consensus m odules on other

servers to ensure that every log eventually contains the

same requests in the same order, even if some servers fail.

Once c ommands are properly re plicated, each server’s

state m a chine processes them in log order, and the out-

puts are returned to clients. As a result, the servers appear

to form a single, high ly reliable state machine.

Consensus algorithms for practica l systems typically

have the f ollowing properties:

• They ensure safety (never returning an incorrect re-

sult) under all non-Byzantine conditions, including

network delays, partitions, and packet loss, duplica-

tion, and reo rdering.

• They are fully functional (available) as long as any

majority o f the servers are operational and can com-

municate with each other and with clients. Thus, a

typical cluster of five servers can tolerate the failure

of any two servers. Servers are assumed to fail by

stopping; they may later recover from state on stable

storage and rejoin the cluster.

• They do not depend on timing to ensure the consis-

tency of the logs: faulty clocks and extreme message

delays can, at worst, cause availability problems.

• In the co mmon case, a command can complete as

soon as a majority of the cluster has r e sponded to a

single round of remote procedure c alls; a minority of

slow servers need not impact overall system perfor-

mance.

3 What’s wrong with Paxos?

Over the last ten years, Leslie Lamport’s Paxos proto-

col [15] has become almost synonymous with consensus:

it is the protocol most commonly taught in courses, and

most imp le mentations o f consensus use it as a starting

point. Paxos first defines a protocol c apable of reaching

agreement on a single decision, such as a single replicated

log entry. We refer to this subset as single-decree Paxos.

Paxos then combines multiple instances of this protocol to

facilitate a series of decisions such as a log (m ulti-Paxos).

Paxos ensure s both safety and liveness, and it supports

changes in c luster membership. Its correctness has been

proven, and it is efficient in the normal case.

Unfortu nately, Paxos has two significant drawbacks.

The first drawback is that Paxos is exceptionally diffi-

cult to understand. The full explanation [15] is noto ri-

ously opaqu e; few pe ople succeed in und e rstanding it, and

only with great effort. As a result, there have been several

attempts to explain Paxos in simpler terms [16, 20, 21].

These explanations focus on the single-decree subset, yet

they are still ch allenging. In an informal survey of atten-

dees at NSDI 2012, we found few people who were com-

fortable with Paxos, even amon g seasoned researchers.

We struggled with Paxos ourselves; we were not able to

understand the complete protocol until after reading sev-

eral simplified explanations and designing our own a lter-

native protocol, a process that took almost a year.

We hypothesize that Paxos’ opaqueness derives from

its choice of the single-decr ee subset as its foundation.

Single-decree Paxos is dense and subtle: it is divided into

two stages that do n ot have simple intuitive explanations

and cannot be understood independently. Because of this,

it is difficult to develop intuitions about why the single-

decree protocol works. The composition rules for multi-

Paxos add significant additional complexity and subtlety.

We believe that the overall problem of reaching consensus

on multip le decisions (i.e., a log in stead of a single entry)

can be decomposed in other ways that are more direct and

obvious.

The second problem with Paxos is that it does not pro-

vide a good foundation for building practical implemen-

tations. One re ason is that there is no widely agreed-

upon algorithm for multi-Paxos. Lamport’s descriptions

are mostly about single-decree Paxos; he sketched possi-

ble approaches to multi-Paxos, but many details are miss-

ing. There have been several attempts to flesh out and op-

timize Paxos, such as [26], [39], and [13], but these differ

2

of 18

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论