SupercheQ:Quantum Advantage for Distributed Databases_P. Gokhale.pdf

免费下载

SupercheQ: Quantum Advantage for Distributed Databases

P. Gokhale,

1, ∗

E. R. Anschuetz,

1, 2, ∗

C. Campbell,

3

F. T. Chong,

1, 4

E. D. Dahl,

3

P.

Frederick,

1

E. B. Jones,

3

B. Hall,

1

S. Issa,

1

P. Goiporia,

1

S. Lee,

1

P. Noell,

1

V. Omole,

1

D.

Owusu-Antwi,

1

M. A. Perlin,

1

R. Rines,

1

M. Saffman,

3, 5

K. N. Smith,

1

and T. Tomesh

1, 6

1

Super.tech, a division of Infleqtion

2

Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

3

ColdQuanta, a division of Infleqtion

4

Department of Computer Science, University of Chicago

5

Department of Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison

6

Department of Computer Science, Princeton University

(Dated: December 8, 2022)

We introduce SupercheQ, a family of quantum protocols that achieves asymptotic advantage over

classical protocols for checking the equivalence of files, a task also known as fingerprinting. The

first variant, SupercheQ-EE (Efficient Encoding), uses n qubits to verify files with 2

O(n)

bits—

an exponential advantage in communication complexity (i.e. bandwidth, often the limiting factor in

networked applications) over the best possible classical protocol in the simultaneous message passing

setting. Moreover, SupercheQ-EE can be gracefully scaled down for implementation on circuits with

poly(n

`

) depth to enable verification for files with O(n

`

) bits for arbitrary constant `. The quantum

advantage is achieved by random circuit sampling, thereby endowing circuits from recent quantum

supremacy and quantum volume experiments with a practical application. We validate SupercheQ-

EE’s performance at scale through GPU simulation. The second variant, SupercheQ-IE (Incremental

Encoding), uses n qubits to verify files with O(n

2

) bits while supporting constant-time incremental

updates to the fingerprint. Moreover, SupercheQ-IE only requires Clifford gates, ensuring relatively

modest overheads for error-corrected implementation. We experimentally demonstrate proof-of-

concepts through Qiskit Runtime on IBM quantum hardware. We envision SupercheQ could be

deployed in distributed data settings, accompanying replicas of important databases.

I. INTRODUCTION

A hallmark of modern networks and databases is dis-

tributed replication of files, whether to improve availabil-

ity, redundancy, or performance. However, replication

requires protocols for integrity verification to check that

copies of data have not diverged. This motivates the

task of fingerprinting: mapping an input bitstring to a

shorter bitstring (the fingerprint) in order to distinguish

two inputs with (arbitrarily) high success probability.

Fingerprinting has been extensively studied in the so-

called simultaneous message passing (SMP) setting [1–3].

In this model, fingerprints of two bitstrings A and B are

sent to a referee to verify whether A = B with high prob-

ability. The goal is to minimize the communication com-

plexity, i.e. the number of bits transferred to the referee,

of this process. Previous work [4] has shown that there

is an exponential advantage in communication complex-

ity when utilizing quantum states for this task. Namely,

for A and B each of N bits, there is a quantum proto-

col that succeeds with high probability using O (log N)

qubits, while there is a known achievable lower-bound of

Θ

√

N

classical bits in performing this task [2]. Un-

fortunately, the protocol of [4] requires constructing a

complicated superposition state that generally takes time

scaling with N to prepare on a quantum computer.

∗

These two authors contributed equally

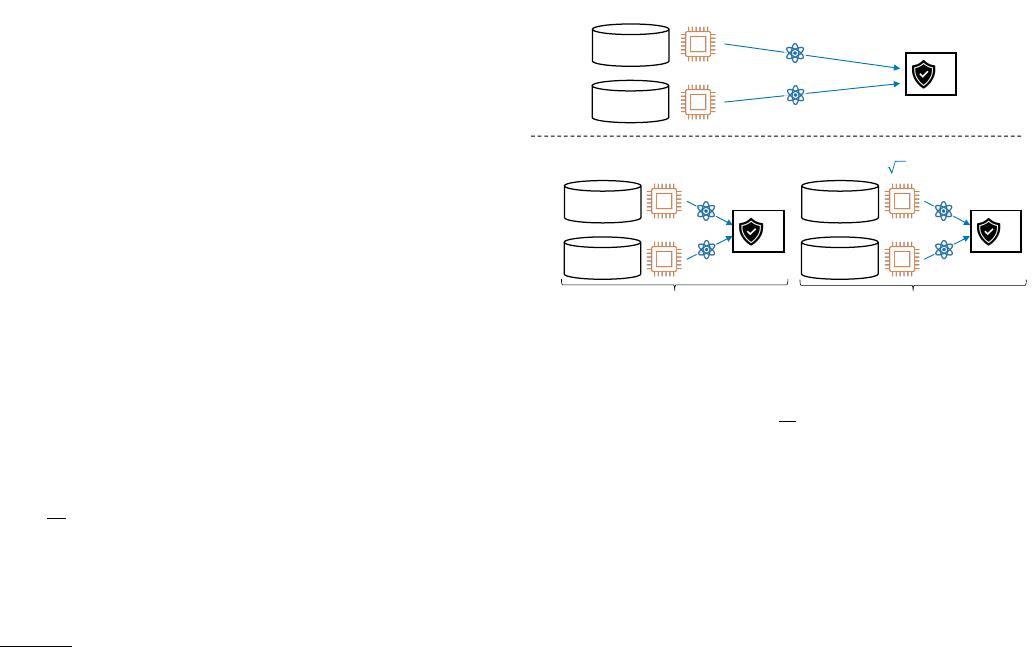

SupercheQ–EE

SupercheQ–IE

101110010…

Alice

(N bits)

101110010…

Random circuit sampling

𝑂(log 𝑁) qubits transmitted.

Or

𝑂(𝑁

!/#

)

with

poly(𝑘)

cost.

Bob

(N bits)

t

0

101110010…

101110010…

?

t

1

Graph state encoding with O(1) incremental updates

𝑂( 𝑁) qubits transmitted.

QPU

QPU

QPU

QPU

?

0

01110010…

0

01110010…

?

QPU

QPU

FIG. 1. The EE (Efficient Encoding) variant of SupercheQ

compares two N-bit files by transmitting as few as O(log N)

qubits—an exponential advantage over classical protocols in

the SMP setting. The IE (Incremental Encoding) variant

matches the best-possible Θ(

√

N) scaling of classical proto-

cols while achieving constant-time updates for incremental file

changes.

To address these difficulties we introduce SupercheQ,

a family of quantum protocols that exhibit asymp-

totic advantage over classical protocols for fingerprint-

ing, as summarized in Fig. 1 and Table I. The first

variant, SupercheQ-EE (Efficient Encoding), achieves an

advantage in communication complexity. This is of-

ten the limiting factor for modern distributed databases.

arXiv:2212.03850v1 [quant-ph] 7 Dec 2022

2

Protocol Hash Quantum FP SupercheQ-EE [§III A, III B, III C] SupercheQ-IE Classical FP Naive

[Example] [SHA-256] [4] [Haar Rdm] [Aprx t-Dsgn] [HW-Eff] [§IV] [3]

FP Size (n) O(1), [256 bits] O(log N ) O(log N ) O(N

1/`

) Empirical

h

∼

√

2N

i

Θ

√

N

,

h

∼

√

3N

i

N

Quantum Cost N/A exp(n) exp(n) poly(n

`

) Empirical O(N ) N/A N/A

Collision-Free? No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Incremental? ?, [No] No No No No Yes No Yes

TABLE I. Comparison of fingerprinting (FP) protocols for files with N classical bits, in ascending order of the fingerprint size.

Quantum cost refers to the gate count needed to produce the quantum fingerprint state. Collision-free refers to whether the

protocol is with high probability safe against worst-case choices of files; in particular, hashing to a constant size (e.g. SHA-256)

is not collision-free because there always exist (many) pairs of files that map to the same hashed value. Incremental refers to

whether fingerprints can be updated in constant time when the underlying file is bit-flipped. We introduce SupercheQ-Efficient

Encoding (EE), which encompasses three subcategories: Haar-Random (§III A), Approximate Unitary t-Design (§III B), and

Hardware-Efficient variant (§III C). We also introduce SupercheQ-Incremental Encoding (IE), which is the only protocol here

that achieves incremental updates.

SupercheQ-EE can be used to check if two 2

O(n)

-bit files

are identical by sending only n qubits, which is an expo-

nential advantage relative to the best-possible classical

protocol. In a nearer-term setting with restricted quan-

tum circuit gate counts and connectivity, SupercheQ-

EE can compare files of size O(n

`

) bits for arbitrarily

large constant `, with quantum circuit cost that scales

as poly(n

`

). For comparison, ` = 2 is known to be the

best that can be achieved classically in the SMP set-

ting [2, 5]. Interestingly, SupercheQ-EE’s core mecha-

nism is random circuit sampling. As such, SupercheQ-EE

endows circuits from quantum supremacy and quantum

volume experiments with the first plausible application

to our knowledge, though current noise rates do not yet

permit a practical advantage.

The second variant, SupercheQ-IE (Incremental En-

coding), matches the ` = 2 quadratic scaling of the best

possible classical protocol, but with the advantage of be-

ing incremental. Specifically, if a bit is flipped in an N-

bit source file, the n = Θ(

√

N)-qubit fingerprint can be

updated in constant time. To our knowledge, no nontriv-

ial classical fingerprinting protocols guarantee this prop-

erty, nor are they likely to achieve this property. The

SupercheQ-IE protocol has two somewhat counterintu-

itive features:

1. The essential ingredient is a Clifford circuit, which

is known to be efficiently classically simulable with

a quadratic memory overhead. However, this

quadratic separation is known to be optimal [6–8]

(i.e. it takes quadratically more classical bits than

qubits to simulate Clifford circuits). As a result,

quantum advantages are known to still persist in

a variety of communication complexity settings, as

recently demonstrated by [7, 8].

2. The protocol does not involve Grover search and

no quantum random access memory (QRAM) is

involved—only an ordinary classical database.

These features are appealing for error-corrected imple-

mentations of SupercheQ-IE. Since only Clifford circuits

are required, SupercheQ-IE avoids the overhead of magic

state distillation for non-Clifford operations [9]. More-

over, no special hardware for classical data loading is

required.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Sec. II provides background on fingerprinting for check-

ing equivalence of data. Secs. III and IV specify the

SupercheQ-EE (Efficient Encoding) and SupercheQ-IE

(Incremental Encoding) protocols, respectively. Since

our asymptotic bounds for SupercheQ-EE are loose,

we employ GPU-accelerated simulation to elucidate

the real-world advantage achievable with SupercheQ in

Sec. V. Next, we demonstrate experimental results for

SupercheQ, executed on IBM quantum hardware, in

Sec. VI. Finally, we conclude in Sec. VII. Appendix A

presents mathematical proofs for key results, and Ap-

pendix B contains additional plots pertaining to noisy

simulation of SupercheQ-EE.

II. BACKGROUND

A. Notation and Setup

Throughout this paper, N will denote the number of

classical bits composing a file of interest, while n will de-

note the number of qubits in the fingerprint. We focus

exclusively on the simultaneous message passing (SMP)

setting [1]. Under this model, we consider the communi-

cation complexity for Alice and Bob to send the finger-

print to a third-party referee, as depicted in Fig. 1. The

SMP setting allows for both Alice and Bob to have pri-

vate coins (i.e., uncorrelated randomness), but assumes

that Alice and Bob do not share a secure random key

(which would require a secure key exchange protocol).

B. Fingerprinting

The most naive classical procedure for fingerprinting a

file is to send the entire file itself. In this case—which cor-

responds to the right-most column in Table I—we have

that n = N . On the other end of the spectrum, we may

of 16

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

评论