Time Series Data Cleaning From Anomaly Detection To Anomaly Repairing.pdf

免费下载

Time Series Data Cleaning: From Anomaly Detection to

Anomaly Repairing

Aoqian Zhang

School of Software,

Tsinghua University

zaq13@mails.tsinghua.edu.cn

Shaoxu Song

School of Software,

Tsinghua University

sxsong@tsinghua.edu.cn

Jianmin Wang

School of Software,

Tsinghua University

jimwang@tsinghua.edu.cn

Philip S. Yu

University of Illinois at Chicago

Institute for Data Science,

Tsinghua University

psyu@cs.uic.edu

ABSTRACT

Errors are prevalent in time series data, such as GPS t rajec-

tories or sensor readings. Existing methods focus more on

anomaly detection but not on repairing the detected anoma-

lies. By simply filtering out the dirty data via anomaly

detection, applications could still be unreliable over the in-

complete time series. Instead of simply discarding anoma-

lies, we propose to (iteratively) repair them in time series

data, by creatively bond in g the beauty of temporal n ature

in anomaly detection with the widely considered minimum

change principle in data repairing. Our major contributions

include: (1) a novel framework of iterative minimum re-

pairing (IMR) over time series data, (2) explicit analysis on

convergence of the prop osed iterative min imum repairing,

and (3) efficient estimation of parameters in each iteration.

Remarkably, with incremental computation, we reduce the

complexity of parameter estimation from O(n) to O(1). Ex-

periments on real datasets demonstrate the superiority of

our proposal compared to the state-of-the-art approaches.

In particular, we show that (the proposed) repairing indeed

improves the time series classification application.

1. INTRODUCTION

Time series data are often found with dirty or imp recise

values, such as GPS trajectories, sensor reading sequences

[15], or even stock prices [16]. For example, the price of

SALVEPAR (SY) is misused as the price of SYBASE (SY),

both of which share the same notation (SY) in some sources.

It is different from the interesting anomaly that actually

happens in real life, e.g., the temperatures sudden change

from 20C to 10C in on e day when cold air rushes in. To

distinguish such cases, we propose to employ some labeled

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy

of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. For

any use beyond those covered by this license, obtain permission by emailing

info@vldb.org.

Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, Vol. 10, No. 10

Copyright 2017 VLDB Endowment 2150-8097/17/06.

truth of dirty observations. (See more detailed examples on

dirty data and their labeled truth in Example 1.)

1.1 Motivation on Anomaly Repairing

Applications, such as pattern mining [17] or classification

[26], built upon the dirty time series data are obviously not

reliable. Anomaly detection over time series is often applied

to filter out the dirty data (see [11] for a comprehensive and

structured overview of anomaly detection techniques). That

is, the detected anomaly data points are simply discarded

as useless noises. Unfortunately, with a large number of

consecutive data points eliminated, t he applications could

be barely performed over the rather incomplete time series.

Recent study [21] shows that repairing dirty values could

improve clustering over spatial data. For time series data,

we argue that repairing the anomaly can also improve the

applications such as time series classification [26]. A repair

close to the truth helps greatly the applications.

1.2 Potential Methods for Repairing

A straightforward idea is to directly interpret the predi-

cation values in anomaly detection, e.g., by AR [3, 14, 27]

or ARX [3, 19], as repairs (see details in Section 2). A d ata

point is considered as anomaly if its (tru th) predication sig-

nificantly differs from (noisy) observation. Unfortunately,

noisy/erroneous data are often close to the truth in prac-

tice, under the intuition that human or systems always try to

minimize their mistakes, e.g., misspellings (John Smith vs.

Jhon Smith), typos (555-8145 vs. 555-8195) as illustrated in

[1], rounding off (76,821,000 vs. 76M) or unit error ( 76M vs.

76B) as shown in [16]. Owing to such disagreement, the re-

pairing performance of directly applying anomaly detection

techniques is poor, as illustrated in both Ex ample 1 below

and experiments in Section 6.

On the other hand, constraint-based repairing SCREEN

[22], strictly following the minimum change principle in data

repairing [1], heavily relies on a proper constraint of speeds

on value changes. The repairing is p erformed based on two

consecutive points, i.e., considering only one historical point,

and thus does not sense the temporal nature of errors. As

shown in the following Example 1, the speed constraint-

based SCREEN is effective in repairing spike errors, but

can hardly handle a sequence of consecutive dirty points.

1046

22

22.5

23

23.5

24

24.5

25

25.5

26

26.5

27

27.5

360 365 370 375 380 385 390 395 400

Value

Time

Observation

Truth IMR

EWMA

SCREEN

ARX

Truth

IMR

SCREEN

ARX

EWMA

Observation

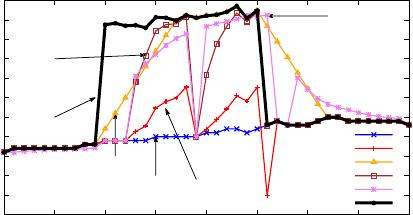

Figure 1: An example segment of sensor readings

In short, the anomaly detection method does n ot expect

the minimized mistakes in practice, whereas the constraint-

based repairing is not effective in addressing the temporal

nature of errors.

1.3 Intuition of Our Proposal

Since completely automatic data repairing might not work

well in repairing t ime series data (such as SCREEN [22] ob-

served in our ex periments in Figure 9), enlightened by the

idea of utilizing master data (a single repository of high-

quality data) in data repairing [9], we employ some labeled

truth of dirty observations to advance the repair. The truth

can be obtained either by manual labeling or automatically

by more reliable sources. For instance, accurate locations

are manually marked in the map by user check-in activ-

ities (and utilized to repair th e imprecise GPS readings).

Moreover, periodical automatic labeling may take place in

certain scenarios, e.g., precise equipments report accurate

air quality data (as labeled values) in a relatively long sens-

ing period, while crowd and participatory sensing generates

unreliable observations in a constant manner [28].

Being aware of both the error nature in anomaly detec-

tion and the minimum change principle in data repairing,

we propose iterative minimum repairing (IMR). The phi-

losophy beh ind the proposed iterative minimum repairing

is that the h igh confi dence repairs in the former iterations

could help the latter repairing. Specifically, IMR minimally

changes one point a time to obtain the most confident repair

only, referring to t he minimum change principle in data re-

pairing that human or systems always try to minimize their

mistakes. The high confidence repairs, together with the

labeled truth of error points, are utilized to learn an d en-

hance the temporal nature of errors in anomaly detection,

and thus generate more accurate repair candidates in the

latter iterations.

Example 1. Figure 1 presents an example segment of sen-

sor readings, denoted by black line. Suppose that sensor er-

rors occur in the period from time point 370 to 385, where

the observations are shifted from the truth, e.g., owing to

granularity mismatch or unit error. To repair the errors,

the truth of several observations are labeled, including time

points {370, 371, 372, 379, 387}.

Existing speed constraint-based cleaning (SCREEN) [22]

could not effectively repair such continuous errors in a pe-

riod (which is indeed also observed in Example 1 in [22]).

The reason is that speed constraints, restricting the amount

of value changing relative to time difference, can detect sharp

deviations such as from time point 369 to 370, but not con-

tinuous errors, e.g., in 383 and 384. The exponentially

weighted moving average (EWMA) [13] algorithm also hard

to find a proper way to clean the trace. These two methods

have similar repair trace.

By considering the predication values in anomaly detection

as repairs (see m ore details in Section 2), the result of AR X

based repairing is also reported. ARX, considering the errors

between truth and observations, shows better repair results

than EWMA and SCREEN methods.

Finally, our proposed IMR approach, with both error pred-

ication and minimum change considerations, obtains repairs

closest to the truth.

The iterative minimum repairing leads to new challenges:

(1) whether the repairing process converges; and (2) how to

efficiently/incrementally update the parameter of the tem-

poral model over the repaired d ata after each iteration. Both

issues in anomaly repairing are not considered in the anomaly

detection studies.

Contributions. Our major contributions in this paper are

summarized as follows.

(1) We formalize the anomaly repairing problem, given a

time series with some points having labeled truth, in Section

2. The adaption of existing anomaly detection techniques

(such as AR and ARX) is introduced for anomaly repairing.

(2) We devise an iterative minimum-change-aware repair-

ing algorithm IMR, in Section 3. Remarkably, we illustrate

that the ARX-based approach (in Section 2) is indeed a spe-

cial case of IMR with static parameter (Prop osition 2).

(3) We study the convergence of IMR in various scenarios,

in Section 4. In particular, the convergence is explicitly ana-

lyzed for the special case of I MR(1) with order p = 1, which

is sufficient to achieve high repair accuracy in p ractice (as

shown in the experiments in Section 6). We prove that under

certain inputs, the converged repair result could be directly

calculated without iterative computing (Proposition 8).

(4) We design efficient pruning and incremental computa-

tion for parameter estimation in each repair iteration, in Sec-

tion 5. Rather than performing parameter estimation over

all the n points, matrices for parameter estimation could be

pruned by simply removing rows with value 0 (Proposition

9). It is also remarkable that the incremental computation

among different repair iterations (Proposition 10) could fur-

ther reduce the complexity of parameter estimation from

O(n) to O(1).

(5) Experiments on real datasets with both real and syn-

thetic errors, in Section 6, demonstrate that ou r IMR method

shows significantly better repair performance than the state-

of-the-art approaches, includ ing the aforesaid anomaly de-

tection and constraint-based repairing.

Table 1 lists the notations frequently used in this pa-

per. All the proofs can be found in the full technical report

(http://ise.thss.tsinghua.edu.cn/sxsong/doc/anomaly.pdf).

2. PRELIMINARIES

This section first introduces the problem of anomaly re-

pairing. We then adapt the existing anomaly detection mod-

els for anomaly repairing, i.e., AR without considering la-

beled data and ARX supporting labeled data.

1047

of 12

免费下载

【版权声明】本文为墨天轮用户原创内容,转载时必须标注文档的来源(墨天轮),文档链接,文档作者等基本信息,否则作者和墨天轮有权追究责任。如果您发现墨天轮中有涉嫌抄袭或者侵权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@modb.pro进行举报,并提供相关证据,一经查实,墨天轮将立刻删除相关内容。

下载排行榜

文档被以下合辑收录

评论